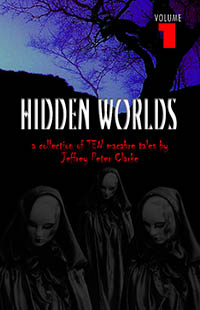

EXTRACT FOR

Hidden Worlds - Volume 1

(Jeffrey Peter Clarke)

Resurrection

No, Alessandro. No!’ Her hand gripped his wrist. Alessandro

wavered, glanced aside at her then lowered the rifle. ‘That officer,’ he muttered angrily,

‘he’s SS. He’s an important man. From here we could pick him off - and maybe

the rest of those damned Nazis.’ ‘No, Alessandro,’ sighed dark-eyed

Carmella. She laid aside her own rifle, leaned against the crumbling stone

wall, eyes turned to the sky above. Late afternoon sunlight filtered through

the pine trees to cast a sheen on her long hair and a dappled pattern across

her face. ‘They’re on the run. Where’s the sense in risking our lives? There

are eight of them and only two of us.’ Stern-eyed Alessandro peered over the

wall, through the trees and across a road of rutted, hardened mud. The officer

was shouting orders and two soldiers, bare-headed, begrimed and sweating in the

heat, emerged from the ancient stone church carrying between them an ammunition

box. This they heaved up into the rear of a drab green truck that had recently

laboured its dusty way up from the direction of the village. Neither the

soldiers nor their officer paid attention to the thud of a distant explosion,

then another, that rolled on sultry air from the south. The explosions had been

going on all day and for much of the day before. ‘That bastard had four of our men

shot,’ growled Alessandro. ‘It’s unforgivable, you know. Unforgivable that we -

that I, should not try to kill them all.’ ‘Look,’ she breathed, placing a hand

on his stubbled cheek,’ the Americans are already in Florence and soon they

will be here. Why risk our lives when others will do the job for us?’ ‘Why?’ he answered, raising the gun

once more, ‘Because they say the Germans are preparing defences to the north.

If they drive back the Americans and the British we’d be for it anyway.’ ‘No!’ she insisted, seizing his arm as

the rifle swung around. ‘Our friends, our families - do you want them to suffer

as well? And what about me, Alessandro? Yes, what about me?’ Alessandro looked into her eyes,

propped his rifle by hers and leaned back against the wall. ‘OK - have it your

way. I suppose we’ve played our part.’ ‘That’s right, Alessandro, we have

played our part.’ Another explosion drifted up from the

valley and as if in response, the truck engine spluttered into life. The

officer was shouting again. Alessandro and Carmella peered through the trees to

observe two soldiers heaving up what appeared to be boxes of files to those men

already in the vehicle then scrambling up to join them. With protesting engine

the truck rattled and lurched forward, swaying along the road, raising brown

dust, coughing black smoke. Two more soldiers, muffled and goggled, weaved

around from behind the church on chattering motorcycles. They steadied

themselves then both raced ahead of the truck. The small convoy revved its way

along the road to vanish from sight beyond the trees. Then silence. Even the shellfire had abated though

beyond the valley way to the south, a dark pall of ragged smoke hung against

the blue haze. Alessandro regarded the smoke then reached into his shirt pocket

to withdraw an all but ruined pack of cigarettes. They were aware now of birds

singing. ‘I suppose,’ said Carmella, ‘we should

tell people in the village the Germans have left the church before we go back

to our homes.’ ‘We can do that,’ mumbled Alessandro,

attempting to light a crumpled cigarette with his battered lighter. ‘I’m not

staying around the valley any longer than I can help. Whoever wins or loses,

I’m going to join the Americans. They might need someone like me - an

interpreter - someone who knows the area and speaks passable English. They’ll

have plenty of cigarettes, too. I hear the Americans always have cigarettes.

You could come with me, Carmella. Yes, I think you should.’ ‘Me? If they’d take us on for good I’d

jump at it. I’d like to go to America, Alessandro - wouldn’t you? Everything is

new there. New and clean and open. We have most of our lives ahead of us. We

could have a fresh start and earn good money.’ ‘We might not see our friends and our

families for a long time,’ he said. ‘You weren’t so bothered about them a

few minutes ago,’ she responded. ‘We can talk about it tonight,’ he

said thoughtfully, blowing out a stream of smoke as he gazed across the

deserted road. ‘I’d like to go as well. They say there’s plenty of work and

good money to be made. Yes, plenty of dollars. We could go together. Yes, we

could get married and go to New York. Better than farming pigs and chickens in

the valley. No more petty feuds, no more family squabbles and no more turning

spadefuls of shit. No more living in the past with ignorant peasants. What

d’you say?’ ‘Oh, yes, I’d like that. Once this war

is over - yes. A new life, Alessandro – all the things we could never have

here. Everything new.’ ‘I’m going to take a look inside the

church,’ he muttered, throwing aside the remains of the cigarette. ‘The Germans

might have left something behind.’ ‘Left something?’ she queried. ‘They

will have taken everything - you see. If there was anything valuable belonging to

the church they will have taken that as well.’ ‘There was never much in that church

from what I remember.’ ‘So you have been inside,’ responded

Carmella. ‘I thought the people from your village never came here. I’m

surprised it hasn’t fallen into ruin.’ ‘We came here once when I was at

school,’ he replied as both picked up their rifles. ‘It was some special

occasion – maybe a saint’s day. I don’t remember what. Everyone used to say it

was too far away even though they preferred it to our new church. The old

village near here was abandoned well over a century ago. It’s all overgrown and

not easy to see from the road. Now the Germans are gone I can show you the

ruins. Maybe tomorrow.’ ‘Why did the people move away?’ asked

Carmella. ‘Why? I’m not sure why,’ responded

Alessandro, slinging the rifle over his shoulder. ‘I heard all sorts of weird

tales when I was at school. Something very bad happened and they were forced to

go. None of the adults ever talked about it. You know how superstitious they

are. I hate all that.’ The thud of two more detonations

rolled dully by. ‘Let’s go,’ said Carmella, shouldering

her own gun. ‘I want to see inside there as well.’ Still cautious, they stepped through

the trees toward a gap in the wall. Alessandro gestured with his hand as they

went. ‘A stray shell landed hereabouts last night - I saw it from my village.’ ‘Oh, well at least it didn’t hit the

church.’ ‘Not the church, no, and not the damned

Germans more’s the pity, and I didn’t see any damage on the road - but I saw

the explosion.’ Pointing to their right he added, ‘Maybe it was over that way -

near the cemetery.’ ‘I think so, too,’ agreed Carmella.

‘Look, there are branches hanging down over there by those old tombs.’ ‘I don’t suppose the residents care about

that now,’ grinned Alessandro. ‘As you say, what does it matter. We

should think of the living rather than the dead. After the war is over I hope

people will do that.’ ‘After the war is over,’ began

Alessandro, ‘you and I will make a new start and -’ Carmella hesitated, her gaze fixed

toward the damaged trees. ‘What is it?’ he asked. ‘Alessandro - there is someone

watching us.’ Alessandro unshouldered the rifle.

‘Watching us - where?’ ‘Look, amongst the trees by those big

old tombs. Don’t you see?’ ‘Ah, yes.’ Alessandro leaned forward,

eyes narrowed. ‘It’s no one I recognise from my village. He looks like a

priest.’ ‘Or a beggar,’ said Carmella. ‘He

could be hurt. Perhaps he needs our help.’ ‘Or escaped from the Germans,’ added

Alessandro as they started through the bushes toward the much overgrown

cemetery. Alessandro slung the rifle over his back and called, ‘Hey, are you

all right?’ There was no reply. ‘The Germans have all gone!’ shouted

Carmella. Still, there was no reply. ‘There’s something wrong,’ said

Carmella as, entering forested gloom, they were obliged to avoid mouldering

gravestones that emerged in tilted disarray from amidst the foliage. ‘He

doesn’t answer us. He doesn’t move. D’you think he’s afraid of our guns?’ ‘Afraid,’ breathed Alessandro. ‘Yes,

he could be afraid. Perhaps he’s a collaborator. If he is a collaborator - well

-.’ Carmella stopped and turned to face

him. ‘Well, what?’ ‘If he’s a collaborator, then -.’ Alessandro

raised his right hand to gesture with finger and thumb the action of pulling an

imaginary trigger. ‘Then nothing, Alessandro! Our own

government was on the side of the Nazis until late last year. We cannot make

such judgements now.’ ‘All right,’ replied Alessandro as

they trudged on, ‘we won’t make any judgements. The people of our villages can

do that.’ ‘Hm, the people,’ muttered Carmella.

‘Most of the people were cheering for Mussolini until a few months ago. Now

listen to them. You’d never believe how much they adored Fascism.’ It was entirely shaded where the

figure stood. He remained motionless as Alessandro and Carmella approached,

much of his face hidden by the cape of a ragged, dark cloak pulled tightly

about his stooping form. The shattered monumental tomb by which he waited gaped

wide - a blackened jawbone set in churned earth, its steps cracked and

mouldering, its soot-laden throat exhaling the corruption of forgotten

centuries. Close by lay the rusted, intricately scrolled ironwork of the gate,

one side shattered where it had been wrenched from its hinges. ‘Are you hurt?’ asked Alessandro as

they halted a few steps away. The old man seemed not to hear the

question. ‘He’s not from my village, either,’

said Carmella. ‘I’ve never seen him before. Perhaps he’s deaf and cannot hear

us.’ For the first time the old man

acknowledged them, casting a pale eye upon the girl. Still he did not speak but

from beneath the cloak a hand emerged to rest upon the broken wall of the tomb.

A pallid, translucent hand with long-sinewed fingers that Carmella regarded

with unease because it reminded her of chicken’s claws. ‘He could be suffering from shock,’

said Alessandro. ‘Perhaps he was walking nearby when the shell landed.’ ‘D’you think we should take him back

to your village?’ asked Carmella. ‘It’s getting late in the day and after dark

he may get lost or fall down.’ Alessandro shrugged and reaching to

place a hand upon the old man’s shoulder asked, ‘Where do you live?’ The old man stiffened, pulled back,

switching his pale gaze to Alessandro as though unwilling to accept the gesture

of friendship. And though his thin lips parted, no sound came. His movement

caused the cape to slip partly aside, revealing more of his face. A gaunt and

shrunken face - a face bearing the toll of ages, with flesh stretched as thin

dry parchment over the scarcely concealed shell of a broad skull. ‘He looks weak and hungry,’ said

Carmella, her face expressing sympathy whilst like a waft of fetid air, a

feeling of revulsion took hold of her. ‘I - I don’t think he can walk very

far,’ she added. ‘He looks starved,’ said Alessandro,

careful not to express his own unease. ‘Perhaps the Germans held him prisoner

for some reason. I say we take him into the church where he can rest for the

night. Tomorrow they can send a doctor from my village.’ ‘You’d better come with us,’ said

Carmella, moving a reluctant step closer to the old man whilst trying to ignore

the odour of damp earth that clung about him. Telling herself her feelings were

irrational, she reached out to place a hand upon his shoulder as Alessandro

almost had but could not bring herself to do it. The old man tottered forward,

his other hand emerging up from beneath the cloak to pinch at the cloth of the

hood which he pulled to conceal that part of his face that had been exposed. ‘I think he has no wish to be seen,’

said Carmella as all three moved hesitatingly away from the ruined tomb. ‘There is no-one to see you!’ declared

Alessandro, addressing the stooped figure loudly as he by now assumed him to be

deaf. ‘The Germans have gone! The road is deserted!’ ‘He doesn’t understand what we say,’

said Carmella. ‘Perhaps he’s a refugee and doesn’t belong here at all.’ They stopped just short of the road,

where the trees thinned out and the old wall lay tumbled amidst long grass. The

old man, covered and hunched almost double as though protecting himself from

the cold and wet that would not arrive until late autumn, appeared reluctant to

go on. Carmella, glad of the opportunity to leave his side, stepped from the

trees, spun about with arms akimbo and confirmed aloud, ‘Look, there’s no one

here! No more Germans! All gone away!’ Ignoring the guiding hand offered by

Alessandro, the old man gasped hoarsely then stumbled into the mellow light of

a lowering sun. With surprising agility he scurried beetle-like ahead of them,

crossing the road to reach the shadows of the solid Romanesque arch beneath

which were set heavy wooden, iron-banded doors. There, appearing little more

than a discarded sack of bones, he leaned against the weathered moulding,

making no attempt to enter though one of the heavy oak doors stood slightly

ajar. Alessandro approached, pushed the door inward to a protest of corroded

iron hinges and creak of time-shrunken timbers then peered cautiously inside. Cool, dim, heavy with a silence that

belied its recent occupation, nothing moved within the vaulted space. Nothing

except a tenuous veil of dust that hung illuminated by a shaft of sunlight

slanting from a small circular window set above the door where they stood.

Discarded boxes lay strewn about the floor but apart from an ancient wooden

chest standing against a stone pier to their right and a small table near the

centre of the modest nave, the interior was devoid of furnishings. ‘OK, let’s go inside,’ said Alessandro. The old man tottered close behind

Alessandro, much of his face still obscured by the cowl from beneath which his

eyes gleamed furtively. Carmella entered last, turning to push the door shut

with a reverberating thud. ‘It doesn’t look as though they’ve

damaged anything,’ said Alessandro, noting as his voice echoed about the stones

that the gilded cloth and ornate candelabra upon the alter at the far end

appeared untouched. ‘Why should they desecrate an old

church,’ remarked Carmella. ‘What good would it do them?’ ‘They’ve wiped out entire villages

when it suited their purpose,’ said Alessandro, gazing about the litter-strewn

floor. ‘Anyhow, we have to consider what to do about our ancient friend here.’ Both glanced around to find the old

man had vanished without their having seen or heard him move from their side. ‘Where’s he -?’ began Alessandro. Then

they observed the figure some distance away beneath the deeper shadows of an

arch. Dark within a greater darkness, the man stood close to the wooden chest,

his cowl pulled back, round and prominent eyes regarding them steadily from an

ashen face. ‘Why doesn’t he say something,’

breathed Carmella, propping her rifle against a pier. ‘The way he stares at us

- it gives me the creeps.’ Feeling a sudden chill in the air she crossed her

hands and rubbed her upper arms. ‘Maybe he’s unwell,’ said Alessandro,

placing his rifle by hers and easing off his small back-pack. ‘I say we make

him as comfortable as we can in here. Someone will come up in the morning.’ ‘Fine,’ agreed Carmella. ‘Then I

suppose we should leave him some food.’ ‘I have bread and cheese, and a few

olives in my pack,’ replied Alessandro. ‘A flask of water, too. He can have

those then we can be on our way.’ ‘The sooner the better,’ said Carmella,

glancing about. A hint of urgency sharpened her words. ‘Once it gets dark we’ll

find it difficult making our way down that churned up road.’ Sunlight no longer streamed through

the high window and Alessandro said, ‘Yes, it’s getting late but we have time

enough. I never thought you were afraid of the dark.’ Carmella pushed back her hair

nervously, glanced at the motionless figure under the arch. ‘No, Alessandro but

I - I feel there’s something wrong.’ ‘Wrong?’ ‘Yes,’ she whispered, ‘the way he

stares at us. It’s as though he’s waiting for something to happen. Something we

don’t know about. Alessandro, we should leave right now.’ Her whispers coiled

into heavy air to spread through the dark vaulting above their heads as swarming

black moths. ‘No problem,’ shrugged Alessandro.

‘We’ll give him the food and go.’ His footsteps rang upon cold

flagstones as with the canvas pack under his arm, Alessandro stepped across the

nave to hesitate by the wooden chest. Eyeing the silent figure, he held out the

bag. ‘You must take this so you have enough to eat and drink when we’re gone.

Others will be here to help you in the morning.’ He would have placed the pack on top

of the chest, for his offer prompted no response, but curiosity took hold and

he reached down to the warped, iron-banded lid. The chest had been deprived of

its lock, which lay broken in the dust at his feet. Alessandro gripped the lid

and pulled. It hinged upward with a sharp squeak. From the obscure interior

arose an odour of mothballs and dry wood. ‘The church vestments are still here,’

he muttered, lowering the pack to the floor then reaching into the chest. ‘You

can use these things to rest on.’ Carmella moved closer, willing Alessandro to

hurry as he lifted a woollen garment from the chest to shake it open before the

old man. ‘Here is a priest’s gown. I don’t think anyone will be needing it for

now. It will keep you warm.’ The old man remained silent as before

though his eyes, becoming much agitated, darted from Alessandro to Carmella.

The eyes burned a cold fire. A fire that seemed to reside nowhere else within

his desiccated frame. ‘Take it,’ said Alessandro, reaching

as though to place the garment about the old man’s shoulders. The gaze switched

to Alessandro, then to the gown. A claw hand raised with shocking suddenness

before Alessandro’s face. The old man’s mouth sprang wide but from it emerged

not words, not a voice in their own or any other language. Through the gloom

spread a hiss like air released from the lid of a long sealed sarcophagus. The

hiss rose in pitch until it became a shriek. Alessandro stumbled back, letting

the garment fall to the floor. Carmella’s voice reached him, shrill and

fearful, ‘Oh, Gesu! Look at him! Look at his teeth! His eyes!’ ‘Gesu,’ breathed Alessandro. ‘Who -

what are you?’ ‘Get away from him!’ cried Carmella.

‘He is loathsome! He is evil!’ Her voice rang through the darkening church,

scurried about stone walls to echo in hollow mockery from vaulted darkness. Alessandro backed to Carmella’s side,

his gaze held by the macabre figure. The hood had fallen away, the ashen face

was fully revealed, hovering above the black gown, a theatrical spectre. Its

mouth set in grotesque parody of a grin, a yawning, reptile grin, a grin of

teeth white as the flesh-stripped ribs of a corpse. The figure started in

silence toward them. Alessandro gasped, ‘Mother of God!’ and stumbling to the

pier where lay their rifles, spun about and seized his gun. Carmella was by his side as the figure

emerged from beneath the arch. ‘Shoot!’ she cried. ‘Alessandro! Shoot him!’ Even as Alessandro squeezed the

trigger Carmella screamed, for the hideous image, gliding as a clockwork doll

upon the flagstones, covered half the distance to them. A crack of thunder and

the air trembled with his shot. The figure reeled, swayed and halted its

advance, eyes wide and unblinking. A piercing hiss sprang from the mouth, both

hands emerged from the gown to spread in anticipation of skeletal embrace and

it started forward again. ‘This is madness!’ cried Alessandro,

seeing from the corner of his eye Carmella raise her gun. The shattering

detonation of her rifle came barely a moment before Alessandro’s second shot,

their flashes combining to illuminate the interior and reveal in one instant a

chamber of stark monochrome, a stone cadaver that harboured blind evil. The

instant filled their vision, expanded and froze to reinforce the horror

confronting them. Hardly had the echo died than the figure swayed and, grinning

widely, resumed its advance. Its laughter shivered the air. A fearful web of

sound that descended about Alessandro and Carmella. ‘To the door!’ yelled Alessandro,

grasping her arm. They stumbled in panic through semi-darkness, on the flesh of

their backs a myriad crawling insects. Alessandro

seized the iron latch, wrenched the heavy door part open, let Carmella free but

dared not to look about because he knew the creature was almost upon him. Close

behind her he pushed through, cold breath prickling his neck, the touch of

something sharp upon his arm. Letting drop the rifle he spun about, hearing her

call his name as his hands fell upon the iron ring. Alessandro heaved with a

strength born of primal fear as the eyes fixed on him from within. A hollow

boom and the door slammed shut. Alessandro gulped twilight air but continued to

grip the ring lest it should be turned by the horror that crouched on the other

side. ‘Hurry, Alessandro!’ came her plea.

‘Hurry!’ Alessandro stared at the ring,

released it, grabbed the fallen rifle and stepped back. In dread fascination

his gaze remained upon the ring lest it should move. Lest the door should begin

to open. ‘Alessandro!’ she called again as at

last he hurried to join her. ‘Alessandro - we must get far away from here! We

must!’ |