EXTRACT FOR

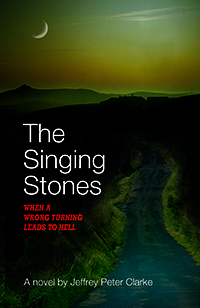

The Singing Stones

(Jeffrey Peter Clarke)

Chapter 1The valley lay nestled within a high land, rising to

meet a sky of soulless embrace. A place laid wide to the elements where here

and there, through a sparse blanket of greenery, earth bared her rocky bones.

Amidst a domain of wind-scoured hills hidden ravines gave forth crystal waters

from nameless regions, bubbling chill life until the hills reclaimed them once

more in dark descent. Unfathomed, blank-eyed

tarns rippled beneath blue skies and rolling clouds. Sometimes the mists

gathered in secret council. Often the rains closed as curtains across an unseen

stage. But on this day the world breathed raw and clear. Seen from above,

sunlight bathed swarming metal ants, for the land was bisected, cleaved by a

hairline ribbon of humanity, a main highway where busy people roared along in

their wheeled cohorts with miles to dismiss, schedules to meet or hopes to

fulfil. *** Only a minute had passed since their vehicle left the

busy main road and the world around was changing. They passed after further

minutes along a deserted country lane that narrowed, imposed upon by

overgrowing hedges, its once unsullied asphalt scarred by numerous potholes and

pierced through here and there by the green claws of nature. Further on they

reached a teetering wooden gatepost from which, its metal head bowed, hung a

flaking green post box. Here they turned onto a dirt track, once, long ago,

considerably wider but edged now by part tumbled rocky embankments. Their

vehicle swayed and crunched wet grit on the deeply descending track. The man

sitting next to the driver, clutching his briefcase, was inwardly apprehensive.

Outwardly he was, when required, and would have to be on this looming occasion,

the official. Always when required he was the official. ‘There used to be a pub not two miles from ’ere,’ said

the driver. ‘Maybe you’ll remember it - the Coach an’ ’Orses. Used to drink

there with my mates in days past. Aye, nice old place it were, too - log fire

an’ all that, as well as good local ale. It’s gone now, though. Aye, no more

than a fond memory. These days there’s nowt for six or

seven miles, maybe more.’ ‘I wouldn’t remember any Coach and Horses,’ responded

the official. ‘I’m fairly new to these parts although it must be getting on for

two years since I moved north.’ ‘It feels t’me even more like the back of beyond than

last time we were ’ere,’ said the driver. ‘These people you’re tryin’ to sort

out, I mean, they can’t ’ave much of a life ’round ’ere can they – don’t you

think?’ ‘I don't suppose they can,’ agreed the official, over

the rise and fall of the engine, ‘at least not the way most people look at

things. We’ve discussed their situation at some length back at the office;

we’ve tried to figure out how best we can help them. I’ve often been asked why

they’re so reluctant to move. And as you say, it can’t be much of a life other

than what most of us would regard as constant drudgery. Take away that old

generator of theirs and I reckon they’d be back in the Middle Ages. The

council’s offered them a fair choice of accommodation at reasonable rent, all

with proper services - you know, central heating, modern kitchen, telephone,

fitted carpets. You’d think at their age they’d welcome a chance to get away

from good old-fashioned hardship and enjoy a taste of modern comfort. There are

people who don’t make any sense to most of us and never will. Oh well, I

suppose it wouldn’t do for us all to be the same – or so others tell me.’ ‘Well y’know what they also say,’ the driver grinned

as they descended the track, ‘there’s no accounting for folk is there – no,

none at all.’ ‘You’re right,’ breathed the official, ‘all too often

there isn’t and it doesn’t make my job any easier.’ Where the ground levelled out they slowed and the

driver, revving hard, shifted gear yet again to guide the vehicle through the

churning black pools of a broad, rubble-strewn clearing. To their right

appeared another wider but much overgrown track. The driver gestured to it,

saying, ‘Meant to ask last time I brought you up ’ere - where’s that lead to?

Can’t be back onto the main road can it? It’s goin’ in’t wrong direction.’ ‘Oh, that - yes, I recall it from our maps,’ replied

the official, ‘it leads down and all the way around the back of the farm to the

quarry entrance. I think this area must be where the workmen parked their

cars.’ They left the clearing and continued, once more

descending, along the rough track until the land again opened out. And now they

had reached the valley, a sheltered area notably more fertile than the higher

land through which they had passed. ‘One thing I will say,’ remarked his driver as the

track began to curve around and the farmhouse with its huddle of outbuildings

came into view yet further down on their right, ‘it can be grand up in these

’ills on a warm summer day but very different in’t winter if you’ve not

experienced it. Looks very pretty ’round this part as well right now, but it

must be ’ard life for anybody wantin’ to ’ang on ’ere all year round if they

didn’t ’ave to. Why, as you say, when your lot are offerin’ ’em the chance of a

decent place in the village with shops close by.’ The engine revved once more. The vehicle rocked,

creaked and lurched onward to trace a wide circle before coming to rest between

the main house and a stone stable somewhat further away. Beyond, to the south,

the land rose in natural limestone terraces before sweeping broadly down

towards the curve of a distant reservoir. ‘Quite so,’ agreed the official once again as he

raised a hand to prod at spectacles shaken down his nose by the motion of the

vehicle. He gripped harder on the briefcase that contained the essence of his

day-to-day working life, saying, ‘Mind you, when I look at those outbuildings I

think there must have been more than just the two of ’em living hereabouts in

years past. A whole family, I’d say, or maybe they could have accommodated

hired labour.’ Hugging a gentle grassy slope within the green valley,

Lower Moss Farm and its several outbuildings grew from the land; limestone grey

beneath shining roof slates. Amid the buildings a modest, sun-glinting lean-to

greenhouse stood in contrast to muted stone. By one wall of the main house was

parked a time-afflicted, drab olive four-by-four. On this occasion the driver

saw fit to inquire, ‘Which of ’em drives that old banger I wonder. Doesn’t look

roadworthy to me.’ ‘I really can’t say,’ replied the official, ‘but I

think it’s probably him. They must use it to get their provisions. I can’t

imagine it ever goes far in that condition and I’d be surprised if the thing is

even licensed let alone insured. That’s none of my business I’m happy to say

but I imagine it’ll be left there to rot eventually with the rest of the place

– if they take my advice and leave, that is.’ A short way to the north of this outwardly placid

enclave spread a substantial grove of ash trees. No great distance beyond the

trees the land arose steeply toward the bleaker Pennine hills, rearing as

monstrous waves, stilled as they began to heave and pile upward in mid-rush to

engulf all before them. Between the farm buildings and the trees lay a level,

netted-off field where a stream-fed pond rippled and geese pecked busily about

in the grass. Somewhat outside this area and higher up on rising ground, a

small number of sheep stood in scattered indifference. Out of sight beyond the

track and the farm, beyond the field to the north-west, lay the disused quarry

that defined the boundary of a world the official was now intruding upon. The

official had noted the quarry on council maps and although he had no interest

in seeing it, its existence had been, in earlier days, of considerable

importance. ‘And you’ve still no idea why they phoned and asked

you to come over ’ere again?’ queried the driver. ‘No, I have no idea whatsoever. I thought the last

time would be it. If they don’t see reason soon, they’ll be left to get on with

their lives as best they can. Trouble is, and you can bet whatever you like on

it; if anything untoward happened to these people, accident or illness, we, the

council that is, would be blamed for not doing enough to help. Yes, it’d be

splashed all over the local papers.’ ‘Serves ’em right I say,’ grinned the driver, ‘but

from what you told me of your last visit, it doesn’t sound as though you’ll see

’em out of there any time soon.’ ‘Possibly not,’ sighed the official, reaching for the

door handle in readiness to step out, ‘but I doubt the powers that be will wish

to waste any more time and effort here.’ The official was at once aware of a cool wind for it

buffeted the car and hissed about the passenger door as he opened it. He

stepped outside, buttoned up his jacket, reached inside the vehicle for his

briefcase and paused for some moments after the engine died to stare with

misgiving at the farmhouse. Through his mind coursed details of those previous

attempts to have them understand what they had no desire to understand while

the woman’s gaze returned to occupy his thoughts. His last visit had been over

a month before. Since then there had been another letter from the council

delivered to their ancient roadside letterbox; an official letter in one of

those regulation brown envelopes most people cared not to see. The letter had

never been answered. People had no business in ignoring official letters. Perhaps it still resided damp and unopened

within that rusted metal husk at the gatepost. But it was that last visit the

official had most cause to remember. He recalled the drizzle and the chilling

wind on his face. Chilling even in those later weeks of summer when elsewhere

the fields were still green, the trees and hedgerows brimming life, the days

still warm and mellow. It had been a final attempt to instil sense, official

sense, into people who had precious little sympathy for the world of

officialdom and its underlings. He had thought about it often since and now

recalled tales of how, in the process of drowning, a whole lifetime might pass

before a person’s eyes. *** ‘I don’t like having to intrude upon you, Mrs

Baxendale, but we are concerned that -.’ ‘Don’t like!’ she exclaimed. The ornately iron grated

fire at the far end of the main room spluttered and spat as if in sympathy with

her words as glowing logs settled. Mrs Baxendale fixed a harsh, pale blue gaze

upon him, her eyes alarmingly magnified behind thick, circular lenses. ‘Don’t

like!’ she repeated. ‘Well, just tell us – what ’ave you not got to like about it? It’s not your ruddy ’ome they’re

tryin’ to force you out of! ’Appen you wouldn’t stand there lookin’ so damned

smug if it were!’ Tightly curled grey hair, a long floral cotton dress

with wide collar and green cotton pinafore gave her the appearance of one yet

to emerge from the realms of a bygone age; an age, perhaps, of post-war

austerity. Her attire matched to staged perfection her husband’s homely,

comfortable armchair image. Mr Baxendale was a moderately flabby man whose once

rugged frame appeared resigned now to the unpitying assault of time. His hair,

thinning, smooth and grey, emphasised a round face of high complexion upon

which glinted rimless spectacles. Stretching over a faded blue-striped shirt,

well-tensioned braces supported baggy, brown corduroy trousers of some

antiquity, the waistband gathered about a paunch nurtured over long years by a

liking for warm ale. Though of lesser height and of slighter build than her

husband, in neither demeanour nor in speech did Mrs Baxendale make any

concession to frailty. Her features might have been sculpted by the wind and

rain; those same elemental forces that had shaped the Pennine hills that

surrounded them. ‘Granite with an abraded porcelain finish,’ was how the

official had once described her features and those same words passed again

through his mind. More so even than those of her husband, her hands were

hardened and callused by toil, her mouth set firm and determined. At all times

did the woman appear determined, her unblinking gaze set as a mask of stern

defiance. Mrs Baxendale stood a little forward of her husband. He had so far

remained silent, drawing occasionally on the well-chewed stem of a rosewood

pipe and dispensing acrid smoke that the official feared would persist to taint

his clothes for days afterwards. Having so bluntly delivered her message, Mrs

Baxendale, stepped abruptly back to stand at her husband’s side and there

waited in tense and challenging stance. ‘Please,’ the official insisted after this charged

interlude, ‘I’m not being smug about anything and we are certainly not and I

repeat, not intending to force you out of your home. But I must try to

have you understand the situation as a part of my job with the council. Mrs

Baxendale, Mr Baxendale, I ask you again, with all due respect, to consider

their proposition. With the quarry closed, the private road giving access to

the track that leads to your property can no longer be maintained, not least

because those few other farms in the area once contributing to it have also

gone – unless, of course, you were able to support the entire maintenance cost

yourselves, which I doubt you’d be in any position to do. This means vehicle

access to your property will become more difficult than it already is and that

is bound to affect any deliveries you may require. How this will also affect

postal services I have no idea at all but there will be no services provided by

the council. And as you’re not online, as you don’t have computer facilities,

you’ll still need to collect your pensions from the post office or bank and

because of closures the nearest branch is several miles from here. Furthermore,

most of this area is to be off limit to the general public because the quarry,

so I’m assured, will become increasingly dangerous. Mrs Baxendale, Mr

Baxendale, the assistance and accommodation on offer are most reasonable.

Please consider what I have said; I’m sure nobody wants to see you suffering

hardship so I would rather you -.’ ‘Them int’ council would rather we just walk out of ’ere,’

cut in her husband, shaking his pipe stem at the official, who took a half step

back to avoid flying droplets as Mr. Baxendale continued, ‘Just give up our

’ome because some chinless little man int’ town ’all puts his ruddy signature

on a few bits of paper and says so!’ The remark was followed by a wheezing

intake of breath and a spate of sharp coughing before he jabbed the pipe stem

angrily back into his mouth with a sharp click. Mrs Baxendale ignored the

interruption, folded her arms defiantly and maintained an unblinking stare.

Hers were hard eyes. Harder by far than her husband’s. His eyes expressed no

small measure of indignation but hers - hers were eyes that held a bitterness

and resentment that went deeper than mere words could express. The official

sensed an anger within her that might have welled from the unmeasured depths of

a Pennine tarn. ‘What do them

in’t town ’all know about folk like us - eh?’ she demanded, ‘What? Lower

Moss Farm’s our ’ome - our liveli’ood. This farm - aye, this farm and the land about it ’as been in my family for

generations. That matters to us! Aye, we’ve worked ’ard all our lives as God

above ’as witnessed and we’ve asked for nowt off nobody. No, we’ve asked for

nowt! Never!’ ‘We’ve asked for nowt from nobody,’ agreed her

husband, adjusting the pipe between tobacco stained teeth with a repeated

click, click, clicking the official found a source of considerable irritation. ‘We owes you and them interferin’ devils out there

nothin’!’ his wife continued. ‘Tell ’im that sits on his damned be’ind all day

and sends letters out he doesn’t know

what makin’ a proper livin’ is! Ask ’im why we’re expected to move rather than

’ave them keep a bit of road in good order. If it were ’is ’ouse I’m sure it

would be put to rights without a second thought.’ ‘Mrs Baxendale, Mr Baxendale,’ breathed the official,

striving hard to appear a model of self-control and conciliation despite inward

feelings of a different nature, ‘the council couldn’t prevent them closing the

quarry because it was owned by a private company, as you well know since it was

originally your land they leased, nor can the council have any responsibility

for maintenance of a privately owned road. All of this is determined by the

economy of this area. I simply want to help you both to resolve a situation

that we feel will become increasingly difficult and -.’ ‘Young man!’ wheezed the husband, wagging his pipe

stem yet closer the official’s chest. ‘Yes, Mr Baxendale,’ sighed the official with his eye

on the pipe. ‘We understand the situation very well as far as you

are concerned. We know the likes of you are just sent out to do the dirty work

for them that doesn’t dare show their faces - them that just sits shovellin’

out letters to folk they ’ope they’ll never ’ave to

face in person. But ’appen me ant’ wife ought to discuss things between

ourselves a while. Aye, sit thaself down while me and Elsie ’as a little chat

int’ kitchen. I’m sure you’ll not mind waitin’ five minutes or so as it must

’ave taken you a fair time to get all the way ’ere fromt’ town ’all anyway.’ ‘No, please go ahead,’ the official replied, wearily.

‘I’ll wait.’ He watched them walk around the solid old dining table

and across the black-beamed room to the rear hallway and noted just beyond,

before the door closed, a flight of stairs rising into shadowed obscurity. ‘Dirty work?’ he muttered. ‘Face them in person? It’s

for their own damned sake I’ve been sent here – not for mine nor anyone else’s.’

The official regarded a rustic armchair positioned close to a shallow alcove

built into the thickness of the wall between the main door and the window. He

stepped over to the chair then, glancing at the door by which the two had just

left, peered at the brown knitted cushion. There were vague stains but no crumbs

and no hairs to be seen so, pulling the chair around and lowering himself

carefully into its creaking frame, he sat close by the small, leaded window

that was neatly framed by red and white gingham curtains. To the other side of

the window stood a diminutive table on which rested an old black telephone with

tarnished chromium dial. He imagined the telephone must no longer work as its

owners had no listed number. He gazed across to high moorland and fading,

treeless hills, some bearing the dark suture of part-tumbled dry-stone walls

that retreated into the monochrome obscurity of a lowering mist. The weather

even lower down in the valley could change quickly. Cold drizzle might sweep in

from the surrounding hills and if the mist thickened the feeling of isolation

would intensify. The vehicle in which he had arrived was visible from the widow

and he could see the driver sitting inside browsing his newspaper. The driver

would be waiting patiently. Perhaps in a while not so patiently. He listened

intently but the voices in the kitchen were too low for him to make out what

was being said. There was within the room a pervading odour. Exuded by

the very fabric of the house it was a hard to define odour of age, of old stone

that somehow reminded him vaguely of a cathedral crypt. Under the low beams,

opposite the window next to where he sat, stood an ancient, heavily carved

sideboard, dark and solid. Upon it resided what in its day would have been

referred to as a wireless set. In deep-lacquered wooden case with a curved top,

intricately patterned front and Bakelite knobs, one of which was part broken

away, it belonged to an age long departed and he wondered if it might be even

older than the two for whom he now waited. He imagined hisses and whistles

issuing from its dusty, valve-cluttered innards as its owners tuned in to hear

in muffled voices, news of air raids over London followed by the measured

gravity of one of Churchill’s wartime speeches. He wondered if the radio would

still pick up broadcasts. Did they

refer to it as a radio? No it was definitely, it had to be, a wireless,

and might now be a collectors’ item even if it no longer worked. There was no

television. This house could not possibly harbour a television. Its presence

would surely be an affront, a blasphemy. Sharing pride of place next to the

radio rested a large black and heavily embossed Bible with metal clasps and

gilded page edges. He wondered which of these items they cherished most, the

radio or the Bible. He decided it was probably the Bible. Yes, apart from a parchment-shaded lamp that hung on

twisted, brown flex from the centre of the ceiling, the old telephone and

wireless set appeared to be their sole concession to the age of electricity. He

could see no newspapers and no magazines; just a few cloth-bound books,

possibly antique, slanted together on a sagging wooden shelf in an alcove to

the left of the stone chimney breast. In the iron grate, the log fire hissed,

flared and once more cracked. His gaze drifted up to the solid oak mantelpiece

above the fire where a Victorian, ebony-cased clock ticked away patiently with

spider hands quivering delicately over spider numerals. Perhaps the radio, the

wireless, did work, or how would they know if the clock was showing the correct

time? Perhaps it no longer mattered. He glanced at his watch and noted that the

clock was some twelve minutes slow. In the space to the right of the chimney rested a

shotgun. Light gleamed upon cold iron barrels and the mellow polished timber of

the stock. No doubt it had accounted for the fate of more than a few birds and

rabbits in the fields and hills thereabouts. Looking up to the ceiling, he

wondered what the two of them ever found to occupy their evenings in the gloom

of those long and often harsh Pennine winters. ‘Chatter to the sheep,’ he heard

himself mutter in an attempt to glean some humour from the situation. But this

old house, the frowning moors and hills, seemed oblivious to witticisms. There

were things here he did not and could never understand. Cosy the room might be

but he found its oppressive out of time character quite alien. The stone walls,

the old furniture; within them slept memories that might stir, might loom large

in those isolated, confining hours of darkness. At other times, when loosed of his official persona,

the official had asked himself if these people were ever young. Had they, could

they ever have experienced or enjoyed the wide-eyed novelties of scintillating

youth? The question fascinated because even he, the official, had often laid

aside his inhibitions amid the sunlit vistas of earlier years. His gaze returned to where the black clock ticked away

countless minutes. Interminable hours. Infinite days. What had it witnessed?

What might it have to tell a world that no longer cared for the intricate,

twitching microcosm that defined its mechanical innards? He thought uneasily

that, if left alone here for long enough, he might fall asleep and awaken to

find himself in another age. Then there was the disturbing sound he had noticed

on an earlier visit – a mournful wailing carried on the wind like voices from

the surrounding hills. He had never asked about the sound because he felt such

curiosity might have compromised his image of detached officialdom. Opening the briefcase he fingered through assorted

papers, lifted out, regarded and replaced his mobile phone. That small item of

day-to-day necessity, more so even than a television, might be a profanity in

this house. He was fumbling in the briefcase for nothing more than reassurance.

His official papers, his mobile phone - these things confirmed his place in a

world that at present felt disconcertingly remote. His was a world of

hierarchy, rules and regulations, a world of schedules, of meetings and digital

communications, a world these people would doubtless find as incomprehensible

as he found theirs. He abandoned his reflections, listened hard once again to

their voices from within the kitchen, closed and lowered his briefcase to the

floor. Their conversation, for the most part hushed and indistinct, was

becoming now more audible. Footsteps. The door creaked and Mr and Mrs Baxendale

reappeared. Odd, he thought. It was as though he was encountering them for the

first time. Perhaps it was because his mind had drifted, because he had allowed

himself to become too relaxed. He now saw them as real people in need of

understanding and help. This would not do. Any sympathies he might acquire

ought to be, no had to be, set aside in the face of official procedure. He

cleared his throat, arose from the chair and stooped to pick up his briefcase. ‘Young man,’ began Mr Baxendale in a low voice. The

pipe had been placed aside. ‘We’ll not be talked into quittin’ our ’ome by no

one. No one - whether you or them rudddy pen-pushers int’ town ’all understands

it or not.’ ‘If they wants to see us out,’ put in his wife,

‘they’ll ’ave to break down’t door and drag us through if that’s what it comes

to! We’ll not give in to none of ’em, see!’ Another tense silence ensued. The official breathed in

deeply. ‘Mr Baxendale, Mrs Baxendale, I have to repeat yet again; no one is

trying to see you out, as you put it. No, it’s not like that at all and it never

has been, but if that is the way you assess things then I’m afraid there’s

nothing more I can do to help. You understand, don’t you, there will be no more

offers of assistance from the council and that’s really not what I wanted to

tell you.’ ‘I don’t give a bugger what you or any of ’em wants or

doesn’t want to tell us,’ growled Mr Baxendale, ‘and I don’t see there’s owt

else to be said ont’ matter.’ ‘Aye, we stay ’as we are,’ affirmed his wife. She

glanced at the main door, adding, ‘So if you don’t mind -.’ The official moved toward the door; a door of stout

wooden planking that opened onto a small porch. There really was no more to be

said as he laid his hand upon the heavy iron latch. From the corner of his eye

he observed them standing together, their gaze fixed steadily on him. As he

stepped out into the rain, there came from behind the voice of Mrs Baxendale.

‘And close the door properly if you would!’ He glanced back into the house as he eased the door

shut. It was her gaze he would remember. A gaze that might have turned him to

stone. |