EXTRACT FOR

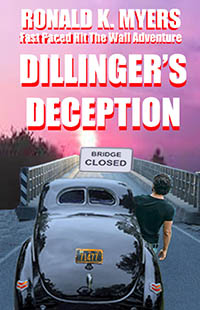

Dillinger's Deception

(Ronald K. Myers)

PROLOGUEIn the

darkness, Ralph squinted toward the low hanging branches of full leaved maple trees.

They seemed to be a black impenetrable wall. He hoped no one was hiding there. A

ways from the wall, two roads triangulated the land he was standing on and led

to the machine-gun-turret protected Jungle Inn Casino. It was 1934. In the

center of the land, a man, the world thought was in prison, stood below a black

and white street sign perched on top of a steel pole. Although the sign read, ‘PETROLEUM’,

no streets ran alongside the sign. Standing

in grass up to his knees and making sure they weren’t

being watched, Ralph surveyed the area. Then he looked up at the sign. “Is this

it, Snorky?” Snorky placed

his hand on Ralph’s back. “Well, Mister Ralph Alsman, can you think of a better

place to keep your money out of the FBI’s hands?” Ralph

took a moment to consider the question. As he watched dim moonlight beam down

on the grass and brush-filled patch of land, he answered. I can’t think of

anyplace better, but I’m still not used to being called Ralph.” Snorky

adjusted the white fedora on his head. “For a million dollars and freedom for

the rest of your life, I think you’ll get used to it pretty quick.” As if

getting to do some serious work, Ralph freed the top button on his white shirt

and loosened his tie. His dark vest fit perfectly, and he seemed to be

comfortable. He smiled a faint smile. “Where do we dig?” “We

don’t.” Snorky

bent over, placed a weird brass key in the base of the steel pole supporting

the Petroleum sign, and pushed. The pole tilted to a forty-five degree angle. He

inserted another brass key at the base of the pole and pushed the pole back to

an upright position. The ground rumbled. Right before Ralph’s feet, a steel

plate slid back revealing a hole with a set of wooden steps. Snorky flicked a

flashlight on and stepped into the hole. “Let’s get your first half of the

million.” When Ralph

followed Snorky into the hole, he descended into one of the many abandoned coal

mines of the area. But a lot of work had been done to this mine. Before them,

at the other side of a concrete floor, a long brass vault, as big as a coffin,

lay on a stone pedestal. Snorky

stepped to the vault and opened it. Except for a brown envelope and a piece of

folded brown paper sewn shut like the string on the top of a dog food bag, it

was empty. Ralph

grabbed the cleft in his chin and gasped. “That folded paper’s not big enough

to hold a half million dollars. Did somebody take the money?” “Looks

like it, doesn’t it?” Snorky gestured to the brown envelope. “If I’m not here, and if by some unforeseen chance your money’s

not here, put an IOU in the vault. That way, I’ll know you’ve been here before

I had a chance to drop the money.” He pointed to the sewn-shut, folded brown

paper. “That’s for the man who took my place in prison. It should be gone when

you come back. Sliding

his hand along the smooth brass surface of the vault, Ralph said, “It seems

such a waste to use a big brass vault just for two little pieces of paper and

an IOU.” Snorky

closed the vault and patted it. “Don’t

judge a vault by its cover. If someone finds your IOU in the vault, they’ll

think you took all the money out.” He reached under the pedestal and pulled out a stone

the size of three bricks. Then, he reached into the opening and pulled out a

long metal box. “Here’s the real vault.” He opened the box. It was filled with

a long line of banded bills. Exhaling a measured breath, Ralph reached over and

ran his hand across the money. Snorky closed the box and handed it to Ralph.

Then he bent over and placed the stone back in the opening below the pedestal. Pointing to the stone, Ralph asked, “Is that where

the other half will be, too?” Snorky stood up and brushed his hands together. “Just

as soon as you’re officially dead, the money will be there.” Gripping the box, Ralph nodded. “Anna’s going to rat

me out. My official date of death will be July 22, 1934.” Smiling, Snorky patted Ralph on the back. “Okay,

Ralph Alsman, after you’re dead, your picture’s going to be all over the front

pages of the newspapers. We don’t want to take a

chance on anyone seeing you after you’re supposed to be dead. Come directly

here and pick up your money.” Even though his picture and the news of his death

were everywhere, on July 23rd, accompanied by a beautiful girl, Ralph drove

a black 1933 Hudson Terraplane Eight to the mine, but someone was already

there. A 1932 Chevy Phaeton with

full white-wall tires and flashing spoke wheels sat alongside of the road. Although it was dark, Ralph

admired the car’s light-blue body and dark blue fenders that ran the length of

the running boards. The

last time Ralph had seen Snorky, the lapels on his tailor-made suit were

hand-stitched. A silk tie had stood out on his white-on-white shirt, and a gold

tie clasp showed the man didn’t go for cheap crap. After

today, Ralph would be able to wear tailor-made suits and wear gold tie clasps

for the rest of his life. He figured the Phaeton was something Snorky would

buy. He proceeded to the mine to see Snorky. When he

got there, a thin man with a mustache was crawling up the steps. As he held his

side, blood flowed from between his fingers. With a pleading look, the man reached

up with his other hand. “Get me out of here.” In an effort to

help the bleeding man out of the mine, Ralph took the man’s hand and pulled. Grimacing

in pain, the man struggled out of the hole and stood up. With labored breaths,

he managed the strength to speak. “Thanks, Ralph.” No one

was supposed to know Ralph was still alive. He wanted to know who the man was.

He looked into the man’s face. “Who are you?” Wincing,

the bleeding man collapsed to the ground. With his arms outstretched and his hands

clawing at the ground, the man’s breath caused blood bubbles to form on his

wounded side. Then the man’s hands quit clawing. His body became motionless. He

was dead. Another

man, with blood trickling from one of the open gashes on his face, walked up

the blood-soaked steps, grabbed the pole, and hung on. Before Ralph

could help the man, a uniformed cop appeared out of the darkness and shouted, “Hey,

jackass, where do you think you’re going?” The man

holding onto the steel pole looked as if he were about to pass out. Apparently

not wanting more injuries, the man cowered next to the pole. The cop reared

back and lifted his huge foot to kick the man from the pole. Ralph

yelled, “Leave him alone! This wasn’t part of the deal.” Instead

of kicking the man, the cop dropped his foot to the ground and lifted his hand.

“Where you’re going, you won’t have to worry about any deal.” In his hand, he

held a police officer issue 38 Colt. He laughed once and fired right into Ralph’s

chest. Ralph grimaced, but didn’t fall over. The cop’s

old 1927 police-issued Colt didn’t have enough velocity

to penetrate the bulletproof vest Ralph had stolen from the police station.

Once again, the vest had saved his life. As if

there were something wrong with it, the cop looked at his Colt. In

pain, Ralph groaned. “What did you do that for?” Surprised,

the cop could only gape. Ignoring

the pain, Ralph turned in fury, pulled his own 38 Colt Super, and emptied it

into the cop. The man hanging on the pole grabbed his side and collapsed. Ralph

made sure the cop was dead and went over and checked the man’s pulse. He was

still alive. Ralph ripped a length of cloth from the dead cop’s shirt and

placed it on the man’s bleeding side. Holding the cloth on the man’s wound, he

looked over his shoulder and shouted toward the beautiful girl sitting in his

Terraplane, “Billie, come here!” Billie’s

lovely legs swished through the tall grass until she stopped at the man’s feet.

Ralph took her hand and placed it on the cloth covering the man’s wound. “Hold

this here. I have to make the withdrawal.” After Ralph

made his way into the mine, he reached under the pedestal, pulled out the

secret stone and pulled out another long metal box. It felt light. When he

opened it, it was empty. Snorky had not made the drop. He put the box back. For a

moment, Ralph studied the big brass vault and wondered why such a worthless

object was secretly entombed in the mine. But he didn’t

have time to worry about it. He hoped Snorky would come back, find out he had

been there, and put the other half of the million in the box. He lifted the vault’s

lid and placed in his IOU. Back up

top, Ralph closed the mine and dragged the cop and the other dead man into the

Chevy Phaeton. Then, Billie and he gently placed the wounded man from the pole

into the Terraplane. Standing

next to the Terraplane, Billie asked, “What do we do now?” “Jump

in the Terraplane and follow me.” Ralph pointed to the Phaeton. “After I get

rid of that, you can pick me up.” Billie

tilted her cute head toward the man in the back seat. “What about him?” “We’ll

drop him off at the hospital.” With

Billie following in the Terraplane, Ralph drove the Phaeton to a place called

Patagonia and stopped at the top of Myers Hill. He placed the car in neutral

and gave it a big push. The Phaeton and the two dead men sailed down the hill

and slid into the deep dark waters of the Shenango River. Even

though the river raged, churned, and twisted around rocks and eroded stony

banks, the Phaeton would stay on the bottom until the spring floods. Then, the

powerful force of tons of water would sweep the Phaeton and anything in its way

downriver. With

his new identity, a half a million dollars, and the FBI no longer after him,

Ralph got married and moved to Oregon. The

vault remained in the mine. CHAPTER 1Thirty years

later, outside the shantytown of Patagonia, Pennsylvania, Freddy Crane walked

around a barrel-sized trashcan overflowing with cardboard containers and

rotting food. As if sweating under the punishing evening sun weren’t

enough agony, roaring amplified by the whining tires came up from behind him. A

hurricane of dust from the slipstream of a huge truck hit him like a hot gale. The

suction wasn’t far from pulling him off his feet. Staring

at the wavy glare of the heat waves that stretched down the tar and gravel

road, he sauntered around the corner. Before

he got to the hamburger stand affectingly called ‘the Burp’ he knew the people

would be falling over one another to be a part of Neal McCord’s humbuggery

action. With

the sun making its late afternoon roll toward the horizon, a pony-tailed girl

with a figure good enough to be on Playboy walked away from a 1950 Ford; and with

a sensual sway, she showboated her way toward the gathered crowd. A teenage boy

beamed an affectionate smile and waved her over. The

crowd was so thick Freddy couldn’t see what they were

watching. The teenage boy turned sideways to talk to the girl. Then, Freddy

knew what everyone was watching. And there he was: In the center of the

blacktopped parking lot. Black hair slicked back, wearing his familiar black

T-shirt, hunched over on his bongo board, rocking side to side on a cylinder of

wood. With his feet spayed and his hips moving to and fro above his

bandy-legged stance, he swayed with the rhythm of the up-beat little tune he

had made up. “Dit-a, dit-a, plonk-oh. Dit-a, dit-a, dit-a plonk-oh!” Neal

McCord’s very existence was something apart from the known properties of a

normal human being. Even though the crazy times of the ‘60s overflowed with

understanding and open minds, Neal was a person Freddy could not understand. At

times Neal was half-boy, half-man. He could become a delusion, a phantom, or a

mirage. At other times, he was welcomed as a savior of a boring situation. With

one hand in his pocket and the other hand waving in the air, Neal looked like a

bull rider; but instead of waving a cowboy hat in his hand, he clutched a wad

of money. “Watch

this.” He flashed his famous Neal McCord smile in the direction of the crowd. “It’s

so easy a pet monkey can do it.” With a single sway of his hips, he rolled the

bongo board on the cylinder until it was at its very end. Bending one leg and holding

the other straight, he stopped the board. Balancing in this unnatural pose, he

threw his arms straight out from his sides and held them there. “See. Nothing

to it.” He grinned. “All you got to do is stabilize yourself by distributing

your weight on each side of the vertical axis.” A

teenager with a cast on his arm and a big scab on his elbow stayed perched at

the end of the parking lot curb. “Yeah, that’s what you told me, and look what

happened.” He held up his arm. A thick white cast coated his forearm. Still

keeping one leg bent and the other one straight, Neal dropped his arms, held

the money in both hands, and thrust it toward the kid. “You

could’ve had half of this.” He shook the money at the broken-armed kid. “All

you had to do was stay on for ten seconds.” He straightened one leg and bent

the other until the board rolled over the cylinder and stopped on the board’s

center. “You want to try it again?” The kid

lowered his broken arm. “I’m not crazy. You make it look too easy.” Neal

fanned the money out and offered it to the fifteen teenagers standing around

him. “Here you go,” he said in a loud, colorful sales spiel. “Get in on the

humbuggery action at the hamburger stand. It’s easy money.” The

pony-tailed girl turned her cute head toward a kid about five and a half feet

tall with jet black hair styled like Elvis. “Come

on, Markey,” she cooed. “You can do it.” Markey

cringed for a moment, but his expression changed to one of a person with a

casual lack of concern. He lifted his hands and held them limply in front of

his chest. “Now, what would I want to do that for?” Neal had

a rhythm to life that gave him an advantage when he wanted to push people off

the ragged edge of their little universe of common sense. With the confidence

of a salesman who had already closed the deal, he lowered his head and lifted

his arms in a what-more-do-you-want-from-me gesture, and looked to Markey. “For

no particular reason.” He flicked his hands down. “That’s why.” With

all eyes on him, Markey exhaled a defeated stream of air. “No reason’s a good enough

reason.” He reached for his wallet. “Here’s five bucks says I can stay balanced

on that thing for five seconds.” In one

motion, Neal swept the money from Markey’s hand. Jerking a wisp of hair away

from his forehead, he winked at the girl. “Hey, everybody likes to be

included.” He tromped on the end of the board. It flew up. He caught it in one

hand and handed it to Markey. Then with the toe of his shoe, he nudged the

cylinder toward Markey. “You’re on.” Markey

put the bongo board on the cylinder, scrunched down, and placed one foot on the

end of the board. With a quick hop, he slapped his other foot on the other end

of the board. Zing! The board flew out from under his feet. Whap! It hit the

blacktop. Markey staggered sideways, but caught his balance. The

girl covered her mouth and muffled a laugh. With a

big ear-to-ear smile on his face, Neal hooked his thumbs into his wide belt and

leaned back. “How many seconds was that?” A big

groan came from Markey. “Very funny.” As Neal

put the five dollar bill in his back pocket, the kid with the cast walked up to

him and stopped. “Come on, man, you know we’ll never stay on your crazy board. Why

don’t we bet on a car race?” Neal

cocked his head to the side, arched his brow, and waved his hand down. “Naw,

naw, naw, racing cars is out. That’s old stuff.” The kid

with the cast made a helpless gesture. “We can’t just stay here and let you take

all our money. You have to do something we can bet on and win.” A look

of hurt streamed from Neal’s baby blue eyes. “You wanted to play. It’s not my

fault you don’t want to win.” A kid

wearing a polo shirt waved his skinny arms. “Is betting on a bongo board all a

garbage man can do?” For a

moment, Neal stood perfectly still and stared at the kid. Freddy

felt a wave of shame crawl over his body. Before he met Neal, he had a low

desire to live. Although Neal and he made pretty good

money hauling garbage, being a garbage

man on the bottom of the success chain wasn’t what he wanted to do all his

life. But it didn’t

bother Neal. Without missing a beat, he waved his hand in the air. “It’s only a

temporary thing, you see. There’s always bigger and better things on down the

road.” “Yeah,

we know,” the kid with the polo shirt said. “Come on, you guys. Let’s quit playing penny ante and do something we can bet

some real money on.” Leaning

against the bulbous fender of a 1948 maroon Plymouth, Neal held his head aloft;

and as if he were searching for an answer, he looked around the parking lot of

the burger stand and sat on the fender. As if on cue, the rusty springs

squealed. He raised his money-filled fist. “I’ll

bet this wad of money.” He thrust his money-filled fist toward the clown-faced

clock under the peak of the burger stand. “All of it.” He paused for effect. “I’ll

bet all of it that we can drive from the Burp to Canada, get a cup of coffee

and a souvenir, and come back in twelve hours or less.” “That’s

three hundred thirty miles one way,” a kid with a broken tooth and thick

glasses said. He tapped his finger in the air as if he were using an adding

machine. “You’ll be lucky to go fifty in that old clunker.” He quit tapping. “And

with no stops at fifty miles an hour, it’ll take you thirteen point two hours.” “Even

if you pull it off,” the kid with his arm in the cast said. “How will we know

you even went there?” As if

he were ready to go, Freddy ran to the Plymouth and jumped into the passenger

side. Neal opened the driver’s side door, sat behind the steering wheel, turned

back to the crowd, and rested his feet on the running board. “I’ll bring back a

Canadian flag and the paid bill for the coffee.” A

skinny kid with red hair combed into a flip, stepped out from under the green

awning of the burger stand and stood next to a 1956 Fireflight Desoto that had

a hideous, two-tone paint job. “That’s

not so great,” he said. “Last week I drove to Cleveland just to get a cup of

coffee.” “So,

what’s the big deal?” a kid with a flattop haircut asked. “Anybody with enough

money could do that.” Neal

stepped out of the Plymouth. Placing each foot just so, quiet

and careful, he moved easy as if he knew just what he had to do. Freddy knew he

wasn’t going to jerk or get wild eyed like a little kid

making up a new lie. He was about to come up with something new. “You

may have a point there,” Neal said. “But I’ve heard that everybody is always

going somewhere. And when they come back they always brag about how great it

was. But the thing is—” He tilted his head toward the kid. “I’ve been told by

reliable sources that in Canada they got the best beer in the world, and all

the bars stay open all night, and you don’t have to worry about drinking too

much and getting into a wreck, cause they have taxi cabs that run somewhere all

the time, and they don’t have half-witted cab drivers that get you lost and

drive you around in circles just to get a bigger fare.” The kid

with the flat-top shrugged. “It doesn’t matter, anybody could still do it.” Neal

hunched over. Using exaggerated strides, he walked around the Plymouth and

stopped at the driver’s side. He held his hand up in a stopping motion. “All

right, gentlemen. If anybody with money can do it, then I’ll do something

nobody has ever done before.” He swiveled his head around and looked at Freddy.

“With no money, we’ll drive to Canada and be back in twelve hours or less.” Freddy didn’t know if such a feat was possible, but if he were

going to share in any money there was to be made, he had to go along with

whatever Neal said. “That’s

right,” Freddy said, and pointed to the road. “Canada and back in twelve hours

or less.” Reaching

into their pockets, a few onlookers stepped closer. “I’ll

take a piece of that action,” one kid said, and pulled out a ten dollar bill.” Bets

were made. Bull, the stocky kid with huge arms, collected the money. The skinny

kid with red hair gave Bull a twenty dollar bill. Then, in great haste, the skinny

kid gave Neal a thumb’s up, jumped into his ‘56 two-tone Desoto, and drove

away. Being

in his usual hurry, Neal jumped into the Plymouth and sat behind the steering

wheel. “Okay, we’re set to go.” He held his hand out, palm up. “Anymore

takers?” Markey

reached into his pocket, but shook his head. “I’d bet more, but I’m on empty.” Neal

turned away from the steering wheel, lifted his arm above the roof, and waved

his hand in a come here gesture. Just as the pink and green neon lights buzzed

on around the top of the white burger stand, a 1940 Ford coupe appeared around

the far corner of the building and coasted into the lot. Neal and Freddy’s

buddy, Rafferty, opened the door and stepped out. Usually,

when Rafferty’s green eyes peered from under his wave in his carrot-orange

hair, he was looking for humor in a situation. When he found it, his contagious

smile would beam across his freckled face; and his skinny body would shudder

with quiet laughter. But this time, his face had a look of seriousness. He

propped his knuckles under his chin, and Freddy could tell Rafferty was trying

not to smile. But he couldn’t do it. As if a light

bulb were glowing over him, his eyes crinkled and a smile spread across his

face. Freddy

looked at the faces of the kids who had bet. Their strained, stunned faces

showed the realization that Neal may have tricked them again. As if they were

paralyzed, they stood with their attention fixed on the Ford. Oohing

and aahing, the non-betting kids gathered around the Ford. “What’s

it got under the hood?” one kid asked, and then the questions and commentary of

the others flowed. “Does

it have overdrive?” “Check

out those new tires.” “Stick

shift, no waiting for an automatic transmission to shift.” “How fast

can it go?” “It

didn’t make any noise when it pulled in; probably got a six cylinder under the

hood.” “Yeah,

probably can’t do over sixty.” “How

come it has Ohio license plates when Neal lives in Pennsylvania?” In a

sliver of shade, Rafferty leaned against the front fender, placed his hands

behind his head, and leaned back. The pony-tailed girl peeked into the side

window and pointed to the radio. “Does that thing get WLS out of Chicago?” Rafferty

smiled an engaging smile. “It’ll get any station you want, sweetie.” In a

show of jealousy Markey stepped between Rafferty and the girl. Before tempers

flared, Neal stepped out of the Plymouth, sauntered toward the Ford, and opened

the driver’s side door. “Okay, Rafferty, let’s get in.” Markey

and the girl stepped back. While Rafferty stepped into the driver’s side and

slid to the passenger side, Freddy ran around and the car and placed his hand

on the door handle. Bull

held up his hand in a halting gesture. “Wait.” Neal held

out his hand. “You got more to bet?” “No,

but we thought you were going to drive the Plymouth.” “Well,

ah, ahem,” Neal said, and gave a negligent wave of his hand. “Sorry, gentleman,

but I didn’t actually say that I was going to drive a Plymouth.” He looked

toward the gathered crowd. “Did anybody here hear me say I was going to drive a

Plymouth?” Markey

looked to Rafferty. “Hey, Rafferty, didn’t you tell me to call on you if I had

a problem?” A

mischievous grin spread across Rafferty’s face. “What about it?” “I have

a problem with you guys switching cars at the last minute. What are you going

to do about it?” Shaking

his head like a simpleton, Rafferty replied, “I told you to call on me, but I

didn’t say I would do anything about it.” Shaking

his head in astonishment, Markey leaned forward in a helpless heap and began

cursing under this breath. As if fooling the kid was an everyday occurrence,

Neal continued, “The bet is that I drive from the Burp to Canada and be back in

twelve hours or less.” Freddy

stepped into the picture. “We never welshed on a deal yet.” Neal

put his hands on his hips. “You want to cancel the bets?” As if

he had been defeated in a game of one-upmanship, Bull’s face turned sullen, but

the kid with the thick glasses stepped up and put his hand on Bull’s shoulder. “Don’t

cancel anything,” he said. “Even if that Ford can do sixty miles an hour, he’ll

have to keep it on those winding roads and not slow down, and he’ll have to

stop for gas that he doesn’t have any money for, and he’ll have to stop to get

the coffee and a bill of sale, that he doesn’t have any money for, and after he

stops at the border, he’ll have to buy a Canadian flag that he doesn’t have any

money for. Even if he had the fastest car in the world he would never make it

in twelve hours.” The kid

with the cast on his arm bent over and looked into the

grill on the front of the Ford. As if he were straining to see inside, he leaned

close to the horizontal bars. “It still has the stock radiator.” He straightened

up and grinned. “If this thing had a new engine in it, they would have had to

change the radiator.” Freddy

knew this wasn’t true, but he wasn’t going to say

anything to spoil their chances of winning the bet. Bull

stared at the kid with the thick glasses. “Are you sure they can’t make it in twelve

hours?” “If he

pushes those six cylinders, he’ll burn up the engine before he makes it to the

border.” Neal’s

bubbly smile sunk. “I don’t know about all those numbers,” he said, and smiled

again. “But we’ll still make it in twelve hours.” “Okay,”

Bull said, with a sly grin. “Just to keep things on the up and up, empty your

pockets, and let me check your wallets.” Neal

reached into his black pants pockets, pulled out his wad of money and some

change, and slapped it on the front fender of the Plymouth. Then he took out

his wallet, opened it, and turned it upside down. “Okay, we’re ready.” “Not so

fast.” Bull held out his hand and jerked it toward Freddy. “You, too.” Freddy didn’t have a wallet, but he walked around the car, turned

out his pockets, and put thirty-five cents on the fender. Bull

turned toward Rafferty. “You’re next.” With his usual smile on his freckled

face, Rafferty handed Bull his wallet, shrugged, and plunked a few bills and

two nickels down onto the front fender of the Plymouth. Bull scooped up the

money and looked up at the clown clock on the peak or the burger stand. The

minute hand that was the clown’s arm, rotated around with its white-gloved

finger pointing to the seconds,” “It’s

two minutes to nine.” Bull said and jerked his head toward the clock. “Twelve

hours from now is nine in the morning, and you’re not going to make it.” Rafferty

made a brusque gesture with his left hand. “What do you mean we’re not going to

make it? What do you think we’re going to do, stop and

play marbles on every street corner?” Bull

smiled. “You might as well.” He shook the bet money in front of Neal’s face. “Take

a good look at it. It’s the last time you’ll see it.” He

let out a deep belly laugh and jammed the money into his pocket. With

the evening bugs just beginning to crash into the buzzing green and pink neon

lights of the burger stand, and girls without dates, wishing someone would take

them to the drive-in movie, watching, Neal jumped behind the wheel of the Ford.

Freddy and Rafferty piled in and waited for him to start the powerful V-8

engine, rack the pipes off, and impress the girls. But he didn’t. Scarcely

giving the hungry engine the gas, he hit the starter. The engine caught and

begged for more fuel. To keep what was under the hood a secret, Neal tried to

pull out of the lot as quiet and as slow as possible, but the powerful engine

growled with awesome power. The kid with thick glasses tilted his head, and scratched

his neck with his index finger. “It sounds like they got a big engine in that

thing. We might lose the bets.” As the

Ford rumbled out of the parking lot, Bull lifted his palms and pushed away from

his body. “No problem. We got it covered.” Beyond

the neon pink triangle peak of the burger stand with the clown’s arm on the

clock sweeping away the seconds, the sun’s last rays peeked through the blowing

tree branches and skittered shut. Without a cent in their pockets and bobbing

their heads to Neal’s stupid ‘dit-a, dit-a, plonk-oh!’tune, Neal, Freddy,

Rafferty, and the bongo board were leaving the gloom of Patagonia’s grassless

backyards spattered with tin cans and dirty-white chickens scratching under

clotheslines where blue work clothes of mill workers flapped under a sullied

sky. They were on their way to Canada. Ten

miles down the road, a huge white sign with black letters read ‘Road Closed

Ahead’. Neal slowed. On the other side

of the sign, a bridge stretched across a wide river. A detour sign, with an

arrow pointed to the road that led to the left. Rafferty

shook his head. “That’s all we need. The other bridge is miles away. It’s going

to be a long detour.” Neal

turned left and tromped on the gas. “We can still make it.” The

Ford rounded a few bends and another detour sign popped up, pointing left

again. Neal rolled around the corner and continued driving at a rapid pace. A

half-mile later, another detour sign pointed left. Neal followed that for a few

miles and stopped at an intersection and looked up. Another detour sign pointed

left. No traffic zoomed past. The road was dark and empty. Rafferty leaned over

and looked at the gas gauge. “Are we running out of gas?” “No,

but I think we’re going around in circles.” Neal turned off the lights. “I just

saw a flash of light. If he’s doing what I think he’s

doing, he’ll come back and see if we took the bait.” Freddy couldn’t understand what Neal was talking about. But before

he could ask Neal about it, headlights flashed in the distance and headed in

their direction. As it neared, the car slowed, but it was too late. Just before

it came to the intersection, Neal flicked the headlights on and swung his hand

down. “Gotch ya!” The ‘56

Desoto that had left the Burp before them approached from the left. Its

unmistakable light blue and dark blue two-tone paint job looked dull and

disgusting. As it passed in front of them, Neal stuck his hand out the window

and waved. As if he were trying to conceal his identity, the driver turned his

head to the side and kept on driving. But the red hair betrayed the skinny kid.

The Desoto’s red taillights faded down the road and Neal laughed with

satisfaction. “That

kid’s old man works for the highway,” he said. “He put up phony detour sighs to

throw us off. We could’ve been driving in circles all night long.” He

turned right and wound out the gears. In no time the Ford’s headlights were

shining on the back of the lumbering Desoto. Under the end of the rounded tail

fins, three taillights looked like short glasses turned on their sides. They

were arranged vertically: one white in the center; and two red: one on top and

one on the bottom. In the center of the almost square trunk, the raised chrome letters

‘Desoto’ spread across a short section above a big shiny chrome V. With

the horn blaring, Neal frantically waved his hand out the window and passed the

heavy car. At the

bridge, Neal hit the brakes and skidded to a stop. He jumped out and kicked the

‘Road Closed Ahead’ sign down. After dragging the sign to the bridge, he bent

over, picked up the sign, and threw it into the river. Brushing his hands

together, he jumped back into the Ford. They were on their way to Canada,

again. On the

dark road, Freddy figured he had to be crazy to be riding with Neal in another

one of his mad, unfathomable schemes that would hurl him into the unknown. He

wondered if there was a chance that Neal could actually make

it to Canada and back in twelve hours, and he wondered how they were going to

get gas with no money. Before he could ask, Neal shut the motor off, coasted

into a dimly lit gas station, and stopped in front of the first pump. Rafferty

turned to Neal. “You got some money hid?” Neal

put his finger to his lips and pointed to the plate-glass window on the front of

the building. Inside, partially hidden behind a pyramid of green and white cans

of oil, the attendant was fast asleep. Neal got out, carefully lifted the gas

nozzle from the side of the red hand-painted pump, and filled the Ford’s tank. Just

as he eased the gas pump’s nozzle back into the slot, a white Pontiac pulled

in. Neal opened the door to the Ford to get back behind the wheel, but paused. He

looked into the station window. The attendant was

still asleep. On top of the towel box a paper garrison hat sat. Neal grabbed it

and placed it on his head. Then he walked to the Pontiac and looked

into the driver’s side window. “Fill ‘er up, and check the oil, sir?” “The

oil’s okay,” the driver said. “Just fill it up.” Keeping

a wary eye on the sleeping attendant, Neal filled the Pontiac and collected the

money. When he went to get back into the Ford, another car pulled in, then

another. He waited on those cars, too, and collected the money. The cars pulled

away; and just as he put the paper hat back on the towel box the attendant woke

up, rushed out the building’s door, and stood in front of Neal. It seemed as if

Neal was going to jump in the car and speed away, but he smiled at the

attendant. “Good

evening,” he said, but there was no tension in his voice. That was Neal: Cool

under any circumstances. He flapped the ends of the money in the attendant’s

face. “I was just coming in to pay for the gas.” The attendant

looked at the dials on the gas pump and then looked back at Neal. “Yeah, I

watched you fill it up.” Freddy

figured they were caught. If the attendant had watched Neal fill the Ford, then

he surely watched him fill the other three cars and collect the money. And on

top of that, to keep from having to get a Pennsylvania state inspection sticker

and pay to have it glued on the corner of the front windshield, Neal had stolen

Ohio plates and put them on the Ford. They weren’t

even out of Pennsylvania and they would be going to jail. But

Neal was one step ahead of the attendant. He held the money in both hands ready

to count off the bills. “How much do I owe you?” The

attendant rubbed his sleepy eyes. “Whatever the pump says.” Neal

paid him and turned to go. Stifling

a yawn, the tired attendant leaned on the pump and crossed his legs. “Thanks,

for being honest.” He stared at the dials on the pump. “I might have my eyes

closed, but I can see right through my eyelids. No one has ever stolen anything

on my shift.” Neal

jumped in the Ford. Sitting behind the steering wheel, he touched his

forefinger to his forehead and gave the kid a lazy imitation of a salute. “Thanks,

for the gas, buddy, and keep up the good work.” He drove off into the velvet

night babbling about how he used to think that it was wrong to steal anything. “What

do you mean?” Freddy interrupted. “It’s still stealing.” “I

don’t worry about it anymore,” Neal said. “Besides, I know this guy from

before. He’s an arrogant son of a bitch who shorted me

on change when I was a little kid.” His eyes glared. “What makes me feel bad is

that the guy’s not going to pay for it. The rich ass oil company’s gonna pay. And

I don’t feel guilty one bit. We’re only taking money

from oil companies and banks and the assholes that got

rich off other people’s misfortunes.” Freddy

sighed, stared at the open road ahead of them, and thought about how he could

convince Neal that no matter how good the reason was for stealing, it was wrong,

but Rafferty interrupted his thoughts. “Okay,”

Rafferty said. “We got the gas and money for more. But we wasted fifteen

minutes back there. How are we going to make it to Canada and be back in twelve

hours?” “Come

on, Rafferty.” Neal reached up, and pretended to be adjusting imaginary

glasses. “It’s easier than balancing on a bongo board. I thought you’d have

figured that out by now.” “What

are you trying to say?” “Back

at the Burp, four-eyes said it was three hundred thirty miles to Canada.” “It

is,” Rafferty said, and cocked his orange eyebrows. “Unless you fly.” “Old

Coke-bottle-bottom-glasses thinks we’re going to cross at Niagara Falls.” A

confident grin spread across Neal’s face. “But we’re going to cross in Buffalo.

That cuts off forty miles, seventy miles an hour into two hundred ninety miles

gives under four hours to get there and under four to get back.” Freddy

spoke from the back seat. “You said you didn’t know anything about numbers.” Neal

put the transmission into overdrive. “It’s all in the game, Freddy. If we had a

straight shot, it would only be about two hundred miles, but it’s

still all in the game. And with overdrive, this Ford will cruise along at eighty-five

with no problem.” He smiled at himself in the rearview mirror. “There’s hardly

any traffic at night. We got twelve hours and can make in under eight.” He

reached over and twisted the chrome knob until it clicked on. The tube-style

radio lit up. Duane Eddy’s Three-Thirty Blues

flowed from the single speaker. Freddy

snapped his fingers and leaned back. “Now we can go to Canada in style.” With

the music blasting into his brain, Freddy felt they might be the only people in

the world who were not imprisoned by wanting to do the familiar and safe things.

Not being afraid of what it would be like to explore something dangerously

different made everything up ahead a brand new raw world of profound mystery. And

they were headed right for it. Neal

thrust the shifting lever into high gear and mashed the gas feed down. For a moment the black unknown ahead swallowed them up. They

flashed past houses, screeched around an elbow bend, rumbled over a set of

railroad tracks, and the radio quit. |