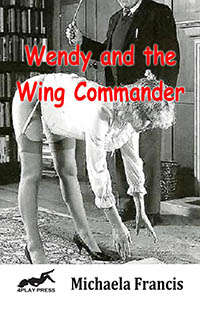

EXTRACT FOR

Wendy and the Wing Commander

(Michaela Francis)

Chapter OneThat

winter I always thought of as my winter of discontent. There were the usual

afflictions of life to deal with. I caught a bad bout of flu in November which

took me nearly four weeks to shake off. The central heating in my apartment

went on the blink in early December and it was over a week before my useless

landlord fixed it. I had the usual problems with my neighbours who seemed to

consider partying until three o'clock in the morning, three times a week, an

acceptable life style. My best friend and closest confidant married and moved

away with her new husband to the far side of the country; about as far away as

it was possible to go without actually heading out to

sea. I missed her terribly. I could have done with her comfort for, just after

Christmas, I broke up with my boyfriend. It wasn't an

acrimonious breakup. I rather wished it had been. If there'd

been heated words and bitter recriminations it might at least have indicated

that there'd been some passion and fire in the relationship. Instead it just

fizzled out without ever catching aflame; whimpered out of existence in dull

tedium and the mutual agreement of two people bored to tears with each other. The most

potent source of my discontent, however, was my writing. My third novel had

been published shortly before Christmas and I was deeply dissatisfied with it

before it even appeared in print. The reviews of the novel didn't

help. It wasn't that they were particularly bad or

anything. They were just bland and uninspiring; rather like the novel itself.

One review described the book as "a pleasant if undemanding read". Another

remarked that it was "light escapist

fantasy; unprepossessing and without any great depth". Yet another commented

that "while not without its charms, the story lacks any real substance for the

reader to get to grips with". Probably the worst review was in a magazine

specialising in historical fiction which dismissed my novel as "rather

ordinary" and then spent the rest of its time picking holes in my historical

accuracy. The reviews depressed me largely because I agreed with them. I had

written the novel to the same basic formula as my first two novels more because

I thought I needed to have another book in print rather than through any real

belief in it. I had taken no risks and it showed. The novel was neither good nor

bad... just indifferent and forgettable. That, in

my depressed opinion, pretty much summed up my writing career to date. I had

enjoyed some modest success but nothing earth shaking. I was essentially

penning pulp romance in a historical setting; Reader's Digest sort of stuff,

diverting enough to pass the time but quickly forgotten about. I risked just

becoming a sort of mindless factory for sugary, trivial romance with every

story pretty much a clone of its predecessors but set in a different era. It frustrated

me because I was convinced that I could do better. Every writer believes that

they have at least one great novel inside them even in the face of all evidence

to the contrary. It's what drives them to keep

writing; that hope that the next book will be the one to explode onto the best

seller lists, receive critical acclaim and be made into a movie. That winter,

however, it was becoming harder and harder to believe that. To grant

him his due, my publisher had not lost faith in me. Indeed he was far more

forgiving of the sub-standard quality of my writing than I was. I was, after

all, he pointed out, still very young. I had just

turned twenty four and to have three novels published by that age was an achievement in itself. Most authors, he told me, didn't hit their peak until much later in life. I was still

forming my style; learning my craft. My writing showed great promise but I couldn't expect to set the literary world alight at such a

tender age. Keep writing he urged me; be patient and it will all come together

in time. Well he

was right of course but it failed to comfort me at the time. In a way, my

writing seemed to mirror the tedium of my life. It was hard to rise to great

heights of imagination and passion while you were mired in a drab world of faulty

central heating, seasonal illness, noisy neighbours, lack of friends and the

breakup of a relationship so dull that you wondered why on earth you had wasted

the past two years on it. How could the heroines of my stories possibly find

excitement and romance in the jaded mind of someone distracted by a negligent

landlord and the monthly electricity bills? By the

time that winter was finally beginning to lose its dismal grip on the world I

was ready to despair; convincing myself that I was a failure as a writer. The

first stirring of spring, however, always bring a renewal of hope and the

resurrection of resolution. I took a long hard look at my writing and made some

firm decisions. To begin with I vowed that my next novel would be a complete

break from my previous works. I needed to take a risk; try something dangerous

and away from my comfort zone. It might turn out to be a disaster but I would

get nowhere by just sticking to the same formula. I decided

as a result to make my next novel a war time romance set during the Second

World War. That was challenging enough for I'd never

tried to write about that period. My first novels had been set in the 18th

and 19th centuries and, to be honest, I'd

borrowed heavily from other writers of the period in my depictions of the eras.

World War Two was new territory for me; scary but exciting. Setting the novel

during wartime held so many more possibilities. I was enthralled by the notion

of a love affair whose intensity was enhanced by the imminent proximity of death.

Would two lovers be constrained from deep commitment by the thought that it

could all end so abruptly in tragedy tomorrow or would they throw themselves at

each other in abandonment to grasp what love they could before some Nazi bomb

or bullet snatched it away from them? I didn't know

but I was eager to explore it. The

trouble was that I knew so very little about the

Second World War at that point. That was a problem because the other decision I

made was that I would no longer be lazy or careless about depicting the era in

which I set my novel. This time, I

vowed, I would do my research properly. I wanted this time to really connect

with the age in which my story was written; to portray it so vividly that the

reader would feel themselves transported back into it and feel a part of its

living reality. That meant that I needed a richness of detail; a familiarity

with every trivial aspect of everyday life. I needed to know what my characters

ate, what they wore, what drinks they would order in the local pub, what they

spoke like, what music they listened to, what sort of transport they used. I

had to know how the war impacted them directly; how they complied with blackout

regulations, what their ration coupons were, how they coped with air raids or

wrote letters through the censors to their loved ones overseas. On top of all

that I had to have a solid grounding in the military campaigns of the war; a

sound chronology of events and how they would affect my story. I needed also a grasp of the technical machinery and jargon of

war; the difference between a Heinkel and a Dornier or between a corvette and a

frigate. Ignorance would be no excuse this time. The world was full of people

who knew their World War Two history inside out and back to front. They would

be merciless towards any howlers I made. Thus, as the crocuses and snowdrops

bloomed in the first week of March I set about my research in earnest. For the

next few weeks I buried myself in my research. I came home from the library

each evening loaded with books. I found myself engrossed in volumes I never

would have thought would ever be on my reading list; a comprehensive guide to

warplanes of the Second World War, a history of the Dunkirk evacuation, an

illustrated guide to British service uniforms of the war and so many more. I

even found myself avidly reading a woman's war time housekeeping guide from

1940 complete with mealtime ration recipes and all the tasty things you could

make with Spam! I went to London and spent a week in the Imperial War museum. From

not knowing much about World War Two, I became obsessed with it. I decided

early to base my book in the summer of 1940. It was, at one and the same time,

both the most dangerous time in Britain and, paradoxically, the most romantic.

It was, of course, the summer of the Battle of Britain; Britain's so-called

"Finest hour" when the country stood alone against the Nazi juggernaut and only

a handful of fighter pilots stood between the nation's freedom and Hitler's

tyranny. It was irresistible; a summer of fear and pride. It was inevitable

that the heroine in my story would be a member of the WAAF (Women's Auxiliary

Air Force) assigned to a front line Fighter Command airfield and fall in love

with some dashing fighter pilot flying daily against the might of the

Luftwaffe. It sounds a little cheesy but I was captivated by a storyline that

hung on such a tenuous thread between happiness and instant tragedy. I tried to

imagine how my heroine would feel every time the squadrons scrambled, knowing

that it might be the last time she would ever see her love. It seems almost

incomprehensible to us now but that was the day to day reality then. How did

people retain hope in the face of the

very real possibility of instantaneous obliteration day after day? It must have

given a sense of immediacy and urgency; the real need to treat every moment of

life as precious and ephemeral. I took a

whirlwind tour of old Fighter Command airfields and Sector Stations from the

battle; places with famous names such as Uxbridge, Hornchurch and Biggin Hill.

Some of them were private airfields or converted into museums but, sadly, some

of them were just derelict and abandoned or built over and redeveloped. I

walked around one such neglected site with a local man. It was mostly used for

grazing sheep by then and what was left of the old runways were cracked and

splintered by weeds. We found the remains of concrete bunkers and the raised

earth revetments in which they used to park the fighters as protection against

bomb blast. A jumble of partially ruined buildings in one corner turned out to

be the old dispersal huts. We walked through them crunching broken glass

underfoot. There was still an old readiness chalk board on one of the walls and

I found an old, framed poster warning of the perils of loose talk with the

misogynist language of an earlier age "Be like dad... keep mum." I was amused by

it so I took it home. You could find a lot of stuff like that lying around

those old airfields in those days. There were even the wrecks of scrapped

aircraft shoved off to one side. Nowadays the places have been pretty much

picked clean by souvenir hunters but back then you could still find these

reminders of the war years. There was

another research resource available to me that is rapidly disappearing now. The

war was still vivid in the living memories of those people who had lived

through it. I spoke to everybody I could find who had experienced the time for

themselves. In some respects it was the most valuable source I had for,

although their memories were sometimes a little sketchy in purely factual

terms, they brought to life the war years for me through their recollections.

It was all in the little day to day details they furnished me with. One old guy

kept me riveted for two hours with his hilarious anecdotes about his farcical

attempts to grow carrots and cabbages in his back yard as part of the nation's

"Digging for Victory" campaign. I won't recount the

story here. Suffice it to say that the Nazi juggernaut had little to fear from

this lovely old man's trowel and hoe. It was stories like that that really

helped me to capture the age. There

was, however, a hidden trap in the anecdotal history of the war that I very nearly

fell into. It is one which I think other students of the war have fallen for

too; one which has helped perpetuate the most pervasive myth about the war in

1940 and leant that particular year its most romantic image. The British, you

see, are such a self-effacing folk that it is easy to make the mistake of

thinking that they were not very good at this war

business when listening to them speak of it. It gives the impression that the

conflict was between this super power of a highly efficient, militarily professional,

ruthless nation up against this little island race of bumbling amateurs,

muddling though and improvising as best it could. It's a lovely "David and Goliath" story that the British

love to tell about themselves. It's all about digging

vegetable plots in the face of Nazi aggression, the Brighton pleasure steamer

sailing off to rescue the boys from the beaches of Dunkirk or Granddad signing

up for the Home Guard and strutting out on parade with a broomstick over his

shoulder because his unit didn't actually have any rifles. It makes for a

captivating story and one which the British have fondly believed ever since. It

is also, unfortunately, almost completely fabricated mythology. At this

point, however, I still believed this jealously protected narrative. The story

of a helpless little island, unprepared and hopelessly amateurish, fighting off

the mighty Nazis was just too appealing. At the risk of getting ahead of myself

in the story, it would be the Wing Commander who would show me the fallacies

behind this myth; that Britain in 1940 mobilised its entire resources for the

purpose of total war more than any other nation on earth, including Germany,

and that, in the Battle of Britain, the bumbling amateurs were the Luftwaffe,

flying, without any real plan, against the most efficient and professional,

integrated air defence system the world had ever seen, with entirely

predictable results. It would be a lesson I would never forget; that real

history is so often occluded by the myths through which we view it. But, as I

say, I am getting ahead of myself. Towards the end of April I was beginning to

feel that I was starting to get the hang of the era and I had the bones of a

story to tell. I was, by then, living and breathing the Battle of Britain. I

had a VCR copy of the movie "The Battle of Britain" and I watched it avidly nearly every day.

There was one scene that even turned me on and you will laugh about this in

hindsight. It was the bedroom scene in which Susannah York struts about without

her skirt on. As you will see before the end of this tale, the irony is not

lost on me. Anyway, just as I was starting to think that I had the beginnings

of a story, disaster struck. Chapter TwoI smelt

the disaster as soon as I turned the corner of my street. There were fire

engines parked outside my house and a pall of smoke enveloping the road. The

smoke was coming from the house in which I had my apartment. I dashed up to my

house in a chill of dread. Everything I actually owned

in the world was in that house. I could be seeing my whole life going up in

flames. Your whole future can turn on a pivotal moment of catastrophe like

that. I guess I was a little hysterical and a kindly fireman had to gently restrain

me from rushing into the house. He made me sit down on the running board of the

fire engine and calm myself. I grasped my head in my hands in despair and I

think I burst into tears. After a

while I collected myself to take an appraising look at the scene. The firemen

seemed to have the fire under control by this time. They were just hosing down

smoking embers now. With a small flicker of hope I realised that the fire had

been largely contained to one of the downstairs apartments. Most of the upper floors,

where my own flat was, seemed relatively unscathed. So it proved in the end. My

own flat and belongings had suffered some smoke and water damage but most of my

possessions were intact or at least salvageable. I had avoided complete loss by

the skin of my teeth. In one

respect, however, the fire had dealt me a severe blow. In its current state,

the house was essentially uninhabitable. The whole place had suffered damage

from the smoke and structural damage from the flames. The windows were broken

and the hoses of the firemen had drenched the floors and ceilings. Without

major repairs and refurbishment, the house was neither comfortable nor safe to

live in. Fortunately my landlord, doubtless worried

about civil lawsuits, turned all conscientious, ethical and sympathetic with

me, in stark contrast to our previous relationship. Eager to retain me as a

tenant, he gave me firm assurances that he would expedite immediate repairs and

would, naturally, suspend all rental payments until the place was fit to live in

once more. He would, he promised faithfully, have the place habitable again

with a few weeks if I could find temporary accommodation for that amount of

time. I already paid a very fair rent but he even offered me a discount on it

for the rest of the year as compensation for the inconvenience. It was, in all

honesty, a very good deal. He even put me up in a

nearby boarding house until I could find somewhere a little better for the

duration of the repairs and allowed me to store my furniture and other bulky

items in his own warehouse. Well it

was most generous of him but I didn't want to spend

anything up to three months in a boarding house so I looked for an alternative.

One immediately came to the fore. Upon hearing of my woes, my sister Josephine,

offered to put me up at her place. It was a bit of a trek because Jo lived up

north in Yorkshire with her husband and two young children but I was grateful

for the kind offer. I loaded my little car with everything I would need and set

off on the A1, the Great North Road, for the north. My sister

and her husband could not have been more hospitable. Jo's hubby was well to do

and they had a big four bedroomed house on the outskirts of Harrogate. Jo made

me up a spare room that was very comfortable. Unfortunately it was not an ideal situation. I was eager,

you must understand, to press on with my new novel after the interruption of

the fire but, congenial though it was, my sister's house was not the place to

do it. I loved my sister well and I liked her husband a lot too. Both of them were more than pleased to have me stay at their

place but it was, when all was said and done, a family house. My nephew and

niece were adorable but they were, after all, very young

children and you can't really explain an author's need for peace and quiet to a

pair of toddlers. A young family household is inevitably going to be a chaotic

place with assorted crises breaking loose several times a day. As a result I

hardly did any writing or research for over two weeks. In fact I spent a lot of

the time babysitting and allowing Jo and her hubby a little break from the

kids. I was pleased enough to do it of course but it hardly helped me get any

work done. I did

manage to get out a couple of times to continue my research. I went with Jo's

family to Eden Camp near Malton which is an old POW camp converted into a

Second World War Museum but it wasn't a particularly

useful excursion since we had the kids in tow and spent most of the time

dealing with potty problems and tantrums. Better was a day when I went out on

my own to visit the Yorkshire Air Museum at Elvington near York. It's an old Bomber Command airfield and a lot has been

restored to its former World War Two condition. The highlight of that day was a

flying visit by the "Battle of Britain Memorial Flight" which overflew us. It

was actually the first time I'd seen a Spitfire or a

Hurricane in flight. The Hurricane looked solid and dependable but the Spitfire

must be one of the most beautiful aeroplanes ever designed and the

characteristic purr of those Merlin engines must have been an evocative sound

in the air over England in 1940. The two fighters were flanking an Avro

Lancaster bomber which I found then, and still find, baffling. What a Lancaster

is doing in a flight commemorating the Battle of Britain is beyond me. The

aircraft played absolutely no role whatsoever in the battle and didn't even come into service until October 1941, over a

year after the battle. Those two

excursions aside, I got very little research done and

even less writing. I was unhappy about this but reluctant to tell my sister of

my dissatisfaction lest she think me ungrateful for her hospitality. Josephine

is a shrewd woman, however, and she soon perceived that all was not well. She

sat me down in the kitchen over a cup of coffee one afternoon and made me tell

her what the matter was. Under her gentle probing, I poured out my concerns. I

think Jo inherited the lion's share of the sympathy and consideration going

among my family's genetic reserves for, far from thinking me a spoiled prima

donna, she was entirely understanding of my problem. Better yet, she had some

wonderful advice. What I

needed, she opined, was to get away some place on my own for a while; some

place where I could concentrate on my writing without distractions. I also

needed, she continued, some source of relevant research material, pertinent to

the era I was writing about. What would be perfect would be a solution that

killed both birds with a single stone and, as it happened, she knew of just

such a solution. She smiled slowly and tapped on the kitchen table, "The person

you need to talk to is the Wing Commander." It was

the first I'd ever heard of Wing Commander Matheson

and I was surprised that my sister knew anybody of that name. She wasn't exactly connected to the military or anything. I

asked her who the devil the Wing Commander was and she told me that he was a

retired RAF Wing Commander who lived in a house on the North Yorkshire coast

between Bridlington and Whitby. The Wing Commander was evidently the owner of

small holiday camp, comprising several holiday chalets and a couple of static

caravans, on the cliff tops overlooking a bay upon which sat a small,

picturesque fishing village. My sister and her husband knew the Wing Commander

because they had spent a fortnight's holiday in one of the chalets the previous

summer. It was a

beautiful spot, my sister assured me, and just the place for a quiet getaway

for a few weeks. The rental on the chalets was very reasonable she told me and

she understood that the Wing Commander also had a couple of cottages in the

village to let for holiday accommodation as well. There was more, however. The

Wing Commander was well known locally because he'd

been a decorated RAF fighter pilot during the war. He'd

even fought in the Battle of Britain itself. He was a lovely gentleman my

sister told me and always keen to tell people about his war experiences. He was

not just an old, retired combat pilot, however. He was an expert on military

and aviation history. After the war he'd been a

lecturer in those subjects at the RAF college at Cranwell in Lincolnshire and

he'd written several books on the topics as well, including, indeed, one of the

most respected and authoritative accounts of the Battle of Britain. If anybody

was qualified to assist me in my research it was the Wing Commander. I would

not only have a welcome break by the sea but also have a gold mine of source

material and expertise at my disposal. The more

my sister eulogised the Wing Commander and the beautiful coastal region he

inhabited, the more interested I became. As we spoke, Derek, my sister's

husband came home and joined us to add his own endorsement. Apparently he'd shared a couple of beers with the Wing Commander in a

pub in the village one evening during their holiday. The old guy was full of

old stories about the war and all sorts of fascinating facts about aeroplanes

and aerial combat. He'd forgotten more about aerial

warfare than most people knew, Jo's husband enthused. Apparently he'd been one of the first RAF pilots to encounter the new

German fighter the Focke Wulf FW-190 in the late summer of 1941 and he'd

described the shock of meeting this hitherto unknown lethal machine to Jo's

husband. Derek agreed with his wife. The Wing Commander was just the person I

needed to talk to. I was

quite naturally excited about all this so, the very next day, my sister dug out

the telephone number for the holiday camp and we phoned up. To my delight they

had several chalets still available to let and a pair of cottages as well. I

asked the prices and I was agreeably surprised. The North of England was much

cheaper than the South and the weekly rental on these chalets and cottages was

not much more than the rent I paid on my flat, in spite of

their being holiday accommodation. I could afford the rent since I wasn't paying for my flat down south currently. I packed up

my belongings and the next day I was heading for the coast. |