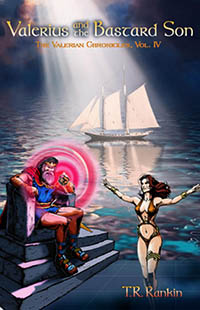

EXTRACT FOR

Valerius And The Bastard Son

(T.R. Rankin)

Prologue

In the months

following the fall of Fantar in the hills east of Palmeria, the remnants of his brutal host-and the regime

they supported-dissipated like a foul mist before the rays of a new day's sun.

They scattered and secreted themselves in hidden corners of the Empire like

damp settling into the timbers of a great ship, and there began to fester and

rot. As the ancient

Imperial order reasserted itself under the High King, Valerius, the worst of

this element were flushed out and dealt with. Some were summarily put to the

sword or cross. Some were sent to the benches of galleys at sea, others to

various dank and dismal gaols. But many-the lower echelons of non-commissioned

officers, men at arms, and the like-were taken at their oath and left to shift

for themselves. Some lucky few of these returned to find home and family,

others drifted to settle here or there, wherever circumstance or the urge to

move on left them. Before Fantar's rise and conquest

of the Inland Sea, many of these men had been brigands and petty outlaws of one

sort or another. Now, some fell afoul of the law yet again. Some fell victim to

their own companions. But one night,on the road north of the tiny town of Koth, just

across from the port city of Palemia on the River

Sule, two in particular fell victim to something

worse. They were not the

most pleasing companions, nor the most sterling of characters. Twenty-year

veterans of Fantar's scourge, they had marched the

entire circuit of the Inland Sea and back under his black flacon banner. They

had fought together in all the major engagements of that time and had seen and

done things even they would not own. Sergeant and NCO, they had belonged at the

last to a regiment of Fantar's Imperial Guard and had

marched eastward with him from Valeria to meet his fate in the dry hills beyond

Palmeria. Not remotely interested in joining their

more fanatical comrades in a fight to the death, these two switched sides early

in the final melee, and afterwards, made good pickings off the corpses of their

former fellows before slinking off in the night and making their way westward. Now they sat late

in a small, mud-walled tavern, their chins sunk low over their cups, and

groused rather too loudly about the fate of their former leader. There were few

customers in the place at this hour-the tavern catered mostly to local farmers,

early risers who had long since stumbled home to their beds-and those few still

scattered about swayed groggily or slumped over their tables. Even the

bartender dozed on his stool, and as the discussion of the two veterans grew

heated, no one seemed to notice their rising volume-no one, that is, except for

the one other upright figure in the room, a hulking youth who sat listening to

every word at a table in the corner behind them. The sergeant had

declaimed on the madness which had seized Fantar near

the end and which had driven him-and his faithful Guard with him-eastward to

the barren hills beyond Palmeria, a full eight

hundred miles from the capital of Valeria. There, under a blistering desert

sun, and at the very start of a battle with the resurgent High King, Valerius-a

battle which the sergeant still claimed they could have won-Fantar

had fulfilled the prophecy by dying at the hand of his Halfling servant, one

who, according to the Oracle, he could only "half see." "Aye"

said the sergeant of the Halfling, "A scrawny little runt he was, not high

enough to kiss your arse... Stuck ole Fantar like a pig, he did." "You

lie!" snarled the youth, suddenly rushing forward and looming over their

table. He was a rough country lad dressed in a farmer's smock too small for his

huge frame. His fisted hands were like hams waving in the sergeant's face, and

while there was as yet but the lightest fringe of down

upon his cheeks, his eyes burned fierce, and anger bristled around him. "Fantar would not die so." But the veteran was

not to be perturbed by such a raw youth, imposing though he was. "Would

not die so? As if his corpse isn't rotting this very moment and himself wailing

away in perdition! And what would you know about it, laddie boy? You were

there, I suppose?" "No, but I

know." "You

know!" the sergeant scoffed, rising to face the youth who still towered

over him. Several other patrons had awakened by now and moved quickly aside.

"You don't know my arse from your mother's dug.

Now go sit down before I... " The youth lunged

over the table, his fingers closing on the veteran sergeant's throat. The two

fell clattering to the floor, thrashing about and upending furniture. In an

instant, the other veteran thrust the broken table aside and flung himself onto

the pair, a dagger glinting dully in his upraised fist. But before he could

drive the blade home, the barman caught his upraised arm. He yanked the man

aside and kicked the other pair apart, then stood over the three brandishing a

large wood axe. "Here!"

he commanded, "There'll be none of that in here. You, Condor, hie yourself

home where you belong. And you two, get your kits and clear out of here. I'll

not have the likes of you wrecking the peace of my establishment!" The youth, Condor,

abruptly fled into the night, the door swinging wide behind him. But the other

pair protested. "What do you mean?" the sergeant whined. "We

were minding our own business here!" "I heard your

talk and I don't like your business," said the barman, brandishing his

axe. "We had enough of 'your business' around here long before Fantar One-Eye got his due. Now clear off I tell you!" "We paid you

for lodging, we did!" claimed the sergeant, thrusting out his chin. "And I'll

lodge this axe in your skull if you push me," growled the barman. By now,

several other patrons, suddenly very sober, had lined up behind the barman.

Some brandished weapons of their own, while others held stools by the legs. The veterans

decided against confronting such odds. Grabbing their packs from the wall by

the door, they marched sullenly out into the night. Nor was this the first time

since Fantar's fall they had been so driven from the

prospect of a comfortable bed. The half-moon was

past its meridian and cast a pale light along the road as the two trudged north

between newly sown fields. They were headed towards a stretch of woods, which

promised fuel for a fire and security for the night. Neither spoke, but both

replayed the scene at the tavern with a growing sense of indignation. So seldom

were they the victims that this incident seemed to justify a host of past sins. "He was a

big-un," said the NCO as the trees began to close around them. "Aye, but

barely a whisker on his chin." "Suppose he's

still lurking about?" "Nah, home to

his mama, more like it. That type has no stick to 'em.

Just keep an eye open anyway." But the sergeant

was wrong. In fact, it was already too late. Behind them, the youth, Condor,

stepped quietly out onto the road, and as the words left the sergeant's mouth,

he smashed a large rock down onto the NCO's head, spattering blood and brains,

and killing the man instantly. "Hey!"

shouted the sergeant flinching away from the spray and spinning to face their

assailant. In an instant he drew sword and dagger and stood crouched at the

ready. "Oh, now you've done it, laddie-boy," he snarled, glancing

quickly at his fallen comrade. "Now you've done it!" And he lunged,

sword whistling in the night air. But the big youth

was quicker. As the sergeant advanced, he hurled the rock. It struck the

sergeant flush in the chest, knocking him back and driving the wind from his

lungs. Then the youth was on him. Grasping both of the man's

wrists, he drove him to the ground and landed on top of him. The sergeant tried

to roll and wrestle himself free, but the youth was too big, too strong for

him. Then he lay still, his arms firmly pinned to the ground by the youth's

massive fists, and glared up into the face of his antagonist. He saw,

momentarily, a look of uncertainty there. "Hah! What are

you going to do now, you bastard!" he spat.

"Move one hand and I'll drive steel into your gizzard so fast you won't

have a chance to blink." Instant fury

contorted the youth's face. His mouth twisted open and he drove his head down,

clamping his jaws onto the sergeant's throat. "Arrgh... !" the man tried to scream, but the sound was

cut short as Condor twisted and bit and ripped at his throat, growling like a

dog. Then he reared his head in the pale moonlight, his eyes raving wild, his

mouth foaming with blood, and the sergeant's dripping larynx clenched between

his teeth. With a strangled cry, he spat the gristle away, lurched to his feet

and ran off into the woods. He ran until the

fury left him, then fell sobbing among the dead and rotting leaves. After a

time, he quieted and lay still until a sound, or something like a sound-it

could have been a rustling in the leaves-trip-hammered his heart and he leapt

to his feet, crouched, tense and ready. He had run far into

a dark, primordial section of the forest. Around him, immense and ancient

trunks mingled with the surrounding shadow, and the late moon cast only the

slightest shimmer through the thick foliage overhead. He could see nothing. Or

could he? There, off to his

right, a bit of shadow seemed to resolve itself against the trunk of a large tree.

Then it moved and he could see the distinct outline of a hooded shape. It

approached silently and Condor looked around quickly for a rock or a branch,

something to use as a weapon. But the figure made no hostile moves. It stopped

about a body's length away and stood there, as tall as himself, slender, yet

still wholly indistinct, a bit of black shadow, shaped from the darkness of the

night. "Who are

you?" Condor demanded. "The question,

my friend, is who are you?" The thing spoke in an unearthly voice, a soft,

sibilant whisper, like a distant wind. "Are you proud of yourself for this

night's performance?" "They had no

right to speak of him thus!" "No right to

speak the truth? Ah Condor," the figure used Condor's name with an easy

familiarity and laughed softly, the sound like scales scraping along a rock,

"you would be a tyrant indeed if you could suppress Truth! But what will

you do now? Go home as if nothing happened? They will soon find the bodies, you

know. You left a rather untidy scene." Condor opened his

mouth but said nothing. He had not thought of anything beyond the urgency of

his rage. Now he pictured the small sod hut that was his home, the old barn and

attached shed, leaning together for support, the figure of his mother, bent and

withered now where once had been a lithe beauty, and the hard, embittered

visage of his step-father, his curses, the beatings. No, if he went back there

now, he would kill him, too. "I can help,

you know," said the figure, as if reading his thoughts. "How? Who are

you?" "Let's just

say I am one who knows who you are... And what you can become. That is what you

want, isn't it? To become like him? You who are twice cursed, the bastard son of a bastard son?" "How can you

do that?" Condor tried to sound derisive, but his voice came out

plaintive. "Ah, there's a

secret, isn't there?" crooned the figure, moving swiftly closer. "The

Truth here, Condor my lad, is that I can make you better than him." And he

leaned towards Condor, the shadow of his hood seeming to envelop his head.

Condor started to pull away, then stopped for just an instant, as something of

the shadow seemed to pass into him. Then the figure was gone and Condor dropped

to the ground like a sack. He was awakened by

a shaft of bright sunlight, which slipped through the leaves and seared his

eyes. Instantly alert, he leapt up and looked around. But the wood was quiet

and peaceful. He had slept late and the sun was well up, dappling the ground

with a golden shimmer. Condor stretched, pulling the muscles tight across his

shoulders and feeling the hardness where they bunched on his arms. Slowly, he

clenched his fingers before his face, curling them into fists. He could feel

power there, and he smiled, a hard, knowing light glinting in his eyes. He made his way

westward, sticking to the forest and moving swiftly but carefully. At a stream,

he drank deep, spitting and rinsing the foul blood from his mouth, then

scrubbed himself clean. Following the course of the stream, he waded in the bed

as it meandered towards the river. Where it crossed the road, he crouched

between its banks looking each way and listening carefully before slipping

across the narrow ford. He was well to the north of where the bodies lay and he

saw and heard nothing. West of the road,

the stream deepened as several other rills joined it and the land tilted

towards the river. The stream tumbled into a larger brook, which cut a deep

gully as it neared the river. When the brook became too deep to wade

comfortably, Condor scrambled along its banks, clambering over large rocks and forcing his way through tangled flood debris,

undergrowth and brambles. Finally, the stream shot out from its banks, tumbled

down a steep fifty-foot rock face and poured into the River Sule. Condor squatted at

the top of the face to catch his breath. He ignored the hollow ache of hunger

in his belly and stared out over the river. The sun was high now, pushing

westward, and the river was broad and deep, nearly a mile across and still

swollen from spring rain in the mountains to the north. The current was swift

and sinewy, flexing like the muscles of a great serpent, too strong to swim.

Directly opposite, the head of an island split the current and beyond, hazy in

the glare of the far shore, was the port city of Palemia. The island, he

knew, stretched several miles to the south, past the town of Koth and almost to

the Inland Sea. Between here and the town, the riverbank was high and the water

deep right up to the shore. No one lived along here until the land subsided,

just north of the town. But that was where the tavern was. Something upstream

caught his eye. It was a large bush, uprooted somewhere in the north and

drifting along towards the sea. As it neared, Condor sprang out like a great

ape, and plunged down fifty feet into the water. Coming up under the base of

the bush, he caught hold of its lower branches and pushed it ahead of him as he

kicked towards the island. Several days later,

in the port city of Palemia, the mate of His Imperial

Majesty's war galley, Steiger, looked up to see a large, hulking youth

amble up the gangway. He was dressed in rough breeches and a loose

smock-farmer's clothes-and looked like he had been sleeping in the woods. But

he had an air of confidence about him, and acted like he owned the boat. "What do you

want?" the mate growled, barring the way at the entry port. "A

berth," said the youth. "A berth? The

war is over these three months past, lad! Everybody else is trying to get

out!" But the youth just stood there, implacable. "Well you look

rugged enough, though a tad young... And it's not like we don't need hands.

What do ye know of seamanship?" The youth stood at

the rail and surveyed the ship from stem to stern, casually taking in her

beaked prow and high forecastle; the long, double-row of benches-empty now with

the crew ashore-and the sweeps neatly lashed; the tall mast and taut rigging;

the square sail tightly furled against the yard; the high poop deck aft with

its tiny cabin tucked below. And he nodded. "I know,"

he said, looking the mate straight in the eye. His eyes were hard and black,

yet somehow compelling. They were the eyes of a much older man, the mate

thought. "Well,"

he said, "let's see what you do know. What do you call that?" he

asked, and pointed to a peg set in the bulwark by one of the benches. Condor looked at

it, the words forming in his mind. "Thole pin," he said. "And

this?" the mate asked, pointing to a similar pin in the rail surrounding

the base of the mast. "Belaying

pin." "And attached

to it?" "Halyard." "All right,

then. Let's see you cast off the main gaskets." Without hesitation,

Condor leaped for the shrouds, hauled himself up the mast hand over hand and

began to loosen the sail. "All right!" yelled the mate. "Belay

that. You may look like a farmer, but there's a right seaman in you, I'll warrant

that." |