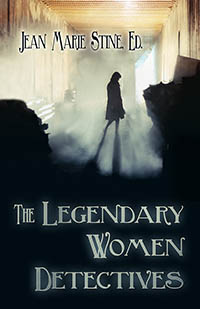

EXTRACT FOR

THE LEGENDARY WOMEN DETECTIVES

(Jean Marie Stine)

INTRODUCTION

In the mystery field, women have

always led and men followed, ever since Anna Katherine Green penned one of the

earliest detective stories, The

Levenworth Case, in 1878 (nine years before Sherlock Holmes 1887

debut). Though men always stole their

thunder – until recently, all the famous of detectivedom were of the male ilk,

Sherlock Holmes, Perry Mason, Nero Wolf – the dames have always been right

there, detecting along side the dicks (public and private),

if overshadowed by them. Thank heaven

all that has changed! Now many of the most popular, bestselling detective

characters are female, and about time.

When readers today are asked to name a famous fictional private eye,

they are more likely to reply "Kinsey Milhone" or "V. I.

Warshawski" than "Mathew Scudder" or even the ubiquitous

"Spencer." Meanwhile, let us not neglect their

nearly-forgotten foremothers and grandmothers in the celebrated cannons of

fictional crime. In days of yore, when

the great Sherlock still strode London's foggy streets, Lady Molly, Violet

Strange, Constance Dunlap, Ruth Kelstern, Solange Fontaine, Madame Storey, and

a legion of their sisters in the detection of crime were on the trail, and like

their masculine counterparts, they always got their man – and often with

considerably more aplomb and adroitness.

Later, in the 1930s and '40s, their successors, like Dol Bonner and Amy

Brewster (available in PageTurner e-book editions), performed the honours with

equal success and skill. This collection resurrects six of

the most memorable of the legendary women detectives, in six of their most

memorable cases. Here is crime in the

day of the Hansom cab, the horseless carriage, the gaslight

and the sputtering new electric kind.

You'll find police detectives, private detectives, even scientific

detectives among these turn-of-the last century female felon-catchers. You'll also find hours of true mystery

reading pleasure as well. Instead of the

old cry in mysteries of "Find the woman!" this is strictly a case

where the Women do the finding. Jean Marie Stine 4/6/2003 THE MAN

IN THE INVERNESS CAPE

BARONESS ORCZY

(Sleuth: Lady Molly)

Lady Molly

is one of three great detectives created by the legendary author of the Scarlet

Pimpernel novels. Her most famous

mystery creation is undoubtedly the Old Man in the Corner (see The Legendary

Detectives Vol. I-II.). But Lady Molly

Robertson-Kirk runs him a close second and is one of the earliest and most

intrepid of women detectives. Lady Molly

joined Scotland Yard to prove the innocence of her husband, who had been framed

for murder and languished in Dartmoor Prison, and to capture the real

killer. Along the way she solved a number of cases which stumped the collective male force of

the CID. Her investigations were

collected as Lady Molly of Scotland Yard (1910). Well, you

know, some say she is the daughter of a duke, others that she was born in the

gutter, and that the handle has been soldered onto her name in

order to give her style and influence. I could

say a lot, of course, but "my lips are sealed," as the poets say. All through her successful career at the Yard

she honoured me with her friendship and confidence, but when she took me in

partnership, as it were, she made me promise that I would never breathe a word

of her private life, and this I swore on my Bible oath "wish I may die,"

and all the rest of it. Yes, we

always called her "my lady," from the moment that she was put at the

head of our section; and the chief called her "Lady Molly" in our

presence. We of the Female Department

are dreadfully snubbed by the men, though don't tell me that women have not ten

times as much intuition as the blundering and sterner sex; my firm belief is

that we shouldn't have half so many undetected crimes if some of the so-called

mysteries were put to the test of feminine investigation. Many

people say – people, too, mind you, who read their daily paper regularly – that

it is quite impossible for any one to "disappear" within the confines

of the British Isles. At the same time

these wise people invariably admit one great exception to their otherwise

unimpeachable theory, and that is the case of Mr. Leonard Marvell, who, as you

know, walked out one afternoon from the Scotia Hotel in Cromwell Road and has

never been seen or heard of since. Information

had originally been given to the police by Mr. Marvell's sister Olive, a

Scotchwoman of the usually accepted type: tall, bony, with sandy-coloured hair,

and a somewhat melancholy expression in her blue-grey eyes. Her

brother, she said, had gone out on a rather foggy afternoon. I think it was the third of February, just

about a year ago. His intention had been

to go and consult a solicitor in the City-whose address had been given him

recently by a friend – about some private business of his own. Mr. Marvell

had told his sister that he would get a train at South Kensington Station to

Moorgate Street, and walk thence to Finsbury Square. She was to expect him home by dinnertime. As he

was, however, very irregular in his habits, being fond of spending his evenings

at restaurants and music halls, the sister did not feel the least anxious when

he did not return home at the appointed time.

She had her dinner in the table d'hote room, and went to bed soon after

ten. She and

her brother occupied two bedrooms and a sitting room on the second floor of the

little private hotel. Miss Marvell,

moreover, had a maid always with her, as she was somewhat of an invalid. This girl, Rosie Campbell, a nice-looking

Scotch lassie, slept on the top floor. It was

only on the following morning, when Mr. Leonard did not put

in an appearance at breakfast that Miss Marvell began to feel anxious. According to her own account, she sent Rosie

in to see if anything was the matter, and the girl, wide-eyed and not a little

frightened, came back with the news that Mr. Marvell was not in his room, and

that his bed had not been slept in that night. With

characteristic Scottish reserve, Miss Olive said nothing about the matter at

the time to any one, nor did she give information to the police until two days

later, when she herself had exhausted every means in her power to discover her

brother's whereabouts. She had

seen the lawyer to whose office Leonard Marvell had intended going that

afternoon, but Mr. Statham, the solicitor in question, had seen nothing of the

missing man. With

great adroitness Rosie, the maid, had made inquiries at South Kensington and

Moorgate Street Stations. At the former,

the booking-clerk, who knew Mr. Marvell by sight, distinctly remembered selling

him a first-class ticket to one of the City stations in the early part of the

afternoon; but at Moorgate Street, which is a very busy station, no one

recollected seeing a tall, red-haired Scotchman in an Inverness cape – such was

the description given of the missing man.

By that time the fog had become very thick in the City; traffic was

disorganized, and every one felt fussy, ill-tempered,

and self-centred. These, in

substance, were the details which Miss Marvell gave to the police on the subject of her brother's strange disappearance. At first

she did not appear very anxious; she seemed to have great faith in Mr. Marvell's

power to look after himself; moreover, she declared positively that her brother

had neither valuables nor money about his person when he went out that

afternoon. But as

day succeeded day and no trace of the missing man had yet been found, matters

became more serious, and the search instituted by our fellows at the Yard waxed

more keen. A

description of Mr. Leonard Marvell was published in the leading London and

provincial dailies. Unfortunately, there

was no good photograph of him extant, and descriptions are apt to prove vague. Very

little was known about the man beyond his disappearance, which had rendered him

famous. He and his sister had arrived at

the Scotia Hotel about a month previously, and subsequently they were joined by

the maid Campbell. Scotch

people arc far too reserved ever to speak of themselves or their affairs to

strangers. Brother and sister spoke very

little to any one at the hotel. They had

their meals in their sitting room, waited on by the maid, who messed with the

staff. But, in face of the present

terrible calamity, Miss Marvell's frigidity relaxed before the police

inspector, to whom she gave what information she could about her brother. "He

was like a son to me," she explained with scarcely restrained tears, "for

we lost our parents early in life, and as we were left very, very badly off,

our relations took but little notice of us.

My brother was years younger than I am – and though he was a little wild

and fond of pleasure, he was as good as gold to me, and has supported us both

for years by journalistic work. We came

to London from Glasgow about a month ago, because Leonard got a very good

appointment on the staff of the Daily Post." All this,

of course, was soon proved to be true; and although, on minute inquiries being

instituted in Glasgow, but little seemed to be known about Mr. Leonard Marvell

in that city, there seemed no doubt that he had done some reporting for the

Courier, and that latterly, in response to an advertisement, he had applied for

and obtained regular employment on the Daily Post. The

latter enterprising halfpenny journal, with characteristic magnanimity, made an

offer of 50-pound reward to any of its subscribers who gave information which

would lead to the discovery of the whereabouts of Mr. Leonard Marvell. But time

went by, and that too remained unclaimed. Lady

Molly had not seemed as interested as she usually was in cases of this sort. With strange flippancy – wholly unlike

herself – she remarked that one Scotch journalist more or

less in London did not vastly matter. I was

much amused, therefore, one morning about three weeks after the mysterious

disappearance of Mr. Leonard Marvell, when Jane, our little parlour-maid,

brought in a card accompanied by a letter. The card

bore the name Miss OLIVE MARVELL. The

letter was the usual formula from the chief, asking Lady Molly to have a talk

with the lady in question, and to come and see him on the subject after the

interview. With a

smothered yawn my dear lady told Jane to show in Miss Marvell. "There

are two of them, my lady," said Jane, as she prepared to obey. "Two

what?" asked Lady Molly with a laugh. "Two

ladies, I mean," explained Jane. "Well! Show them both into the drawing-room,"

said Lady Molly, impatiently. Then, as

Jane went off on this errand, a very funny thing happened; funny, because

during the entire course of my intimate association with my dear lady, I had

never known her act with such marked indifference in the face of an obviously

interesting case. She turned to me and

said: "Mary,

you had better see these two women, whoever they may be; I feel that they would

bore me to distraction. Take note of

what they say, and let me know. Now,

don't argue," she added with a laugh, which peremptorily put a stop to my

rising protest, "but go and interview Miss Marvell and Co." Needless

to say, I promptly did as I was told, and the next

few seconds saw me installed in our little drawing room, saying polite

preliminaries to the two ladies who sat opposite to me. I had no

need to ask which of them was Miss Marvell.

Tall, ill-dressed in deep black, with a heavy crape veil over her face,

and black-cotton gloves, she looked the uncompromising Scotchwoman to the life. In strange contrast to her depressing

appearance, there sat beside her an over-dressed, much behatted, peroxided

young woman, who bore the stamp of the theatrical profession all over her

pretty, painted face. |