EXTRACT FOR

The Dimbo Patrol

(John Klawitter)

THE DIMBO PATROL - EXCERPTJOHN KLAWITTER THE BA MUOI BA BLUES Back home, that is, Stateside/ A

six-pack of Bud A case of Old Rheingold/ Will clean

out the crud. But here by the Mekong/ There's no

Coors or Blatz The only beer sold here/ Will pickle

the rats. Formaldehyde brew/To your native

sons true, Ba Muoi Ba, Ba Muoi Ba, BA MUOI BA

BLUE. Ma Death took your buddy/ Pa Rot got

your shoes. The forecast is stormy/ The war's

the bad news. Learn meditation/ Your outlook's

confused. Lost in translation/ The way back

refused. And that's why they call it/THE BA

MUOI BA BLUES. Formaldehyde brew/To your native

sons true, Ba Muoi Ba, Ba Muoi Ba, BA MUOI BA

BLUE. The bush an' the border/ Is no place

for fools Hold tight to your teddy/ The family

jewels As long as they're playin'/ THE BA MUOI BA BLUES. I'll go to the C.O./ And here's what

I'll say, "Just let me go home now/ I

don't want to stay." "There's short-time in Sidney /

Some kangaroo wine In Bangkok or Hong Kong / the blow

jobs are fine. But there'll be no Pan Am/ No flight

to L.A. Til you nail Victor Charley/ In the

old muddy clay." Formaldehyde brew/ To your native

sons true, Ba Muoi Ba, Ba Muoi Ba, BA MUOI BA

BLUE. - Crazy Jack Beale & Mad Denny

Haller, Saigon, 1964 AFTER IT WAS OVER…December, 1965. Talk

about a quick change that could make you go crazy. Six weeks after he got on

the Pan Am 707 that flew him back from Saigon to Travis AFB near Oakland, Beale

is honorably discharged out of the army.

Back home in Chicago he lucks into a cub copywriter job at Leo Burnett,

a blue-chip ad agency famous for home-spun Mid-American humor, good

old-fashioned patriotism and down-to-earth, long-running campaigns for wholesome

products like Kellogg’s breakfast cereals, Green Giant frozen vegetables,

Campbell soups, Nestles Chocolate, Nescafe coffee, Pillsbury cake mixes and

lots of other All-American products. So a few months after he got back from his

war he is living in a cartoon world of his own creations, a half a step away

from his own brand of PTSD. Back then PTSD wasn’t really a thing, so he is

just flying solo out there, crazy as a baboon on dope. This is Jack Beale,

idealistic loony who tossed away a fellowship in Grad English at UCLA to see a

war like his idol Hemingway was supposed to have done back in World War I. Fucking Beale, the guy who – the few friends

who had seen him off to the Orient figured – wouldn’t know the difference

between a rice peasant and a VC terrorist.

But once he got back it was a different story not really in a good way,

with confusing signs. On the one hand, his mad passion for creativity caught on with the marketing crowd. They even called him

a true creative genius in our midst in an article in ADVERTISING AGE,

the trade weekly that made a big deal about such things. And yet, there was something not quite right

about Jack Beale. One frosty winter morning two unwittingly laconic Chicago

cops sitting in a big Ford patrol car eye him over their steaming coffee, newly

poured from a big thermos bottle close at hand.

“Pencil-neck geek bumbler on your left,” the one says. “Wanna toss him?” “Nah. Let’s see if a

bus or a truck runs him over.” “My money’s on truck.” “You’re on.” John Kennedy is a couple years dead with a bullet or two in

his head and Vietnam is as out of control as runaway inflation. Meanwhile, Beale has already been and is

back. Here he is in Chicago’s loop

marching through swirling snow flurries along busy Randolph Street, puffing

clouds of steam as he goes. He’s wearing

a Peter Max t-shirt, tattered blue jeans sticking out from under his olive-drab

army greatcoat, his feet wrapped in worn rubber-soled sneakers, coat

unbuttoned, long blood-red woolen scarf and matted, sun-bleached hair whipped

by the raw wind pouring off the iced-over edges of Lake Michigan. The cops are amused, bored, nothing much

going on, downtown Chicago frozen stiff, barely moving. “Maybe we should toss him a little? See he’s got any mary-jane? “No, I ain’t going out there.

He could freeze his nuts off by hisself.” “Look at him. Slush

up to his ankles and he don’t got on no socks, neither.” “I blame it on Elvis.” “You blame everything on Elvis.” “Well, I’m right.

Sonny Bono. Doris Day. Rock Hudson.

What kind of names is those? What

ever happened to Schmidt, Kolowalski and DeAngelo?” Mindy Minkle, junior copygirl on Lilt moves to the far side

of the elevator as Beale shakes snow off his coat and out of his long, straggly

blond hair. “Hey, stop!” she says. “Sorry. I can’t seem

to get enough of the cold.” “Enough?” She

inspects him, “You idiot! Your ankles

are blue.” “They’re just ankles.” “You are such a mistake.” There’s no answer for that as the shiny aluminum doors

whisper shut. At the last minute a hand

reaches in, followed by the rest of Beale’s boss, Carl Nixum,

a big guy even bigger swaddled in a greatcoat of his own, only his is thick

black cashmere and doesn’t have a fleck of snow on it. He looks Beale over with measured reserve, like he’s

observing some strange fish swam in from the coral reefs of Australia. Carl was in WWII, a real war. He can’t figure Beale out, wants nothing to

do with him, but has to tolerate him because his own boss said so. “Beale. You got my Korny Rooster copy yet?” “Nope. You said you

don’t need it for two weeks, remember?

You’re leaving for Los Angeles today.” Nixum’s thick brows knit. For a moment he looks like he wants to take a

swing at Beale. But then he shrugs it

off; turns to Mindy, bursts into song, “I

cleaned the windows and I swept the floor/and I polished up the handle of the

big front door.” She grins and picks up on it, “He polished up that handle so carefullee...” And they finish together, “That now he is the ruler of the queen’s navee!” Nixum gives her that frowning dark look of his, finally breaks

into a smile. “Off-key, but commendable enthusiasm.” Mindy clears her throat, “Sir, I’d love to write a Korny Rooster assignment for you.” “Well, see Beale here about that.” The bell dings and Nixum moves his

rolling thunder off the elevator. “Well, Beale? How

about it?” “Stick to vaginal products.” Her face reddens.

“Hair spray isn’t—“ But Beale is already out of the elevator and three steps

down the hall. A half hour later Chris Larson, Nixum’s

girl-Friday, pokes her head in Beale’s cluttered cubicle. “Got that Korny copy yet?” She gives him gruff, letting him know she’s in charge, right

hand to the creative lord, the gal who knows her job and takes no crap from

ordinary copy rats. Beale just wants her out of his office so he can do some

serious creative thinking. But he sees

she isn’t going easy. “What, boss-man sent you to spy on me?” Chris is pudgy, pink-faced with pouty lips and short blond

hair that cups her round face. Beale

thinks she looks like a lemon cupcake.

Lemon is one of his least favorite things. Stacked like a brick shit-house, the guys say behind her back. Lard

ass. “I just need to know when we can squeeze that one stinking

sixty second radio commercial copy out of you,” she says. “It’s not like farts, you know.” “Eeuu,

gross.” Beale is trying to put rooster radio out of his mind. Corny Rooster is a tired old formula; you put

some sleepy people in a goofy situation like flag pole sitting or sleep walking

in traffic and Korny comes along and wakes them up

with a refreshing bowl of corn flakes. “Ahh, hem,” Chris

says. “I’m still standing right here,

and I’m not going away.” A twitch starts at the right corner of Beale’s lip, a weakness

from a round of Bell’s Palsy when he was a kid.

He knows he has to get rid of the bitch or the tick will move on to his

eyelid. His unfocused gaze drifts around

his cubicle, past the cut-out cardboard planes, blimps and trains he’d

fashioned for Pop Tarts, finally settling on the bright red rug tacked to his

back wall. “See that rug?” he says.

“That’s a Montagnard marriage blanket.

You turn down a man who owns one, you’ll be without joy or love, and

childless for life, to boot. Childless

for life. ” “That’s a load of crap, Beale. I don’t think so.” But her eyes flick to the

back wall. She’s thinking Beale is a

whacko-bird; you never know what he’s going to do. God, if

Nixum would only get up the balls to fire him! Beale jumps from his chair and turns to the wall; he trails

the fingers of his right hand almost reverently across one of the ornate

stitched symbols, petting the fabric as if he is summoning juju or demons. “You don’t know anything,” he tells her. “A man simply wraps it around the woman he

selects and they are married. Here, I’ll

show you.” Push-pins fly in all directions as he rips the silk

rectangle from the wall, a dramatic gesture; he drapes it around his shoulders

and starts toward her. “Let’s give it a try.

We’ll be married in the eyes of God, and maybe the secretary pool will

give you a shower.” “No! Stop it,

Beale! You’re just too weird for words.” “Oh, we’re past words, Baby!” She tries to keep her cool, but weird Beale is coming around

his desk, eyes shining over the rim of the odd blanket with its scary primitive

designs, voodoo or whatever they are.

Some asshole chuckles from a nearby cubicle. No help there. Chris can’t take any more. She gives out a

little wail and retreats down the hall, her chubby, mini-skirted thighs

flapping, her head-banded hippie au natural look draining to pure middle

class white girl panic under the florescent overheads. The Nestles’ creatives are looking for a new campaign – new

name and everything – for a chocolate bar and Beale is thinking Oou La La, Ecstasy Malted, the bar that begs to be

bit. He knows the candy creatives

will probably steal it, but it’s a funny idea, has a tasty sort-of sexy image

going. He’s sitting at his Selectric, fired up to get it down on paper when Mindy Minkle

walks in, biting her lip, glaring at him. “I’ve just been to Nixum’s

office. He says he was serious. You have to give me the Corny assignment.” Beale doesn’t look up from his typewriter. “Okay.

Go ahead.” “No,” she tells him.

“You have to assign it.” He slaps the hard top of the Selectric,

spins a half circle in his chair, facing her. “Okay. Korny is sitting on the toilet, taking a dump.” “Be serious. We can’t

do that on television.” “Sure we can. Do it discrete. Cut to the cereal logo - ” “Beale, this is radio.” “Right. Even better.

Okay, we hear a flush and Korny pops his head

out of the toilet bowl and that becomes a cereal bowl and –“ She pushes his cluttered in-box off his desk and storms out

of his office. Beale knew the drill, and two hours later when Nixum wandered by, snapping his fingers and stopping as if

he’d suddenly remembered the Korny copy, Beale had it

ready for him. Nixum frowned at the copy, looking for something. “How do we establish the guy is sleepwalking? This is radio, you know.” “Easy: Traffic noise.

Horns. Passerby says, ‘That guy

is walking in his sleep!’” “Yeah…that’ll work.” By this time Nixum is in Beale’s

small cubicle, sitting on the filing cabinet next to Beale. “What the hell is that stuff?” He waves at a brightly colored mobile of

cartoon planets and space ships hanging from the ceiling. “Promo idea for Fruit Puffs.

Fruity Boy in outer space.” “Odd…” “That’s why you put up with me.” Nixum frowns. “Don’t talk like that.

I only put up with you because I have to. What the hell is that stuff over there?” He points to a cluster of hand written paper scraps pinned

on a cork board in one corner of Beale’s back wall. Nixum reads out

loud and his tone is sarcastic, ‘The

leper's bad eye hung from its socket and the whitish, rotten stumps of his

elbows and knees peeked through rag wrappings, and yet he grinned up from his

home-made skateboard with a fierce, indomitable cheerfulness.’ “I’m writing a novel,” Beale

tells him. “I don’t want you doing

that. I own you. I want you to eat, sleep and breathe Korny Rooster. You

got extra time, you shit Korny Rooster!” The big man waves the copy in

Beale’s face and storms out of the cubicle. “So do you,” Beale mutters behind

his back. Nixum

turns, his face red, his thick eyebrows lowered. “What did you say?” “Shit ‘til I’m blue,” Beale says. About that wanna-be

Nam novel Beale is trying to write: he

scribbles the horror and the madness whenever it comes to him, and push-pins

his scraps on his cubical walls next to the cereal boxes and the storyboards

for his Swiss chocolate village. The

jingle he’s come up with goes: They’re bringin’

them down from Choc’lit town Those Nestles bars They’re bringin’

them down from Choc’lit town Those Nestles bars They’re bringin’

them down so golden brown ‘Cause

Nestles Makes The Very Best Chooooooc’

lit! It makes for an odd mix, stories about blind people and

maimed vets next to happy messages about candy bars and sugar coated

cereals. Beale is for spontaneity over

organization; he writes his real stuff on

bits he’s torn from copy assignments, on the backs of paychecks, on toilet

paper, on scraps ripped from the Chicago Tribune. Old pastel fliers touting cheaper dry

cleaning and new restaurant openings, his ideas crowded on their blank back

sides with his cramped, impatient hand, and in the end all these bits and

scraps are piled pell-mell in his desk drawers, crumpled in his pockets,

paper-clipped in rumpled stacks, tossed in shoeboxes or in the major mess that

his old army footlocker has become. And yet for some reason unknown to himself, he cannot force

himself to go back and pull it all together into that novel he wants to write

more than anything, though he's tried a hundred times. He will clean his desk, unplug his phone, and

clear his weekend so he can work on it.

But his inner truth, the basic reality he cannot admit even to himself,

Jack Beale can only take the past in little peeps and doses. He will no sooner sit down to get started on

chapter one when the images of that other time leak out, slowly at first and

then more and more like a stream of hot tracers, ripping open the old wounds in

his mind until he has to stitch his mortally wounded past back together and

stagger away. Beale and the art director assigned to him are at a dimly

lit Chinese restaurant on Michigan Avenue a few blocks from the agency. Beale

frowns at the big brown egg roll on the plate in front of him. Some city workers had been drilling the

sidewalk, but they have taken off for lunch and the place is quiet. Henri grins at him and orders another Hamms

beer. He points to Beale’s egg roll.

“Can’t compare to the original, huh?”

Henri has the gift, a magic wrist. The man can really draw, not like most ADs

who just fake it with imagine this

and some blather about maybe visualize it sort of like this, the not-magic

wrists going with a lot of waving. Henri

is in his early 50’s and he can draw fast, in practically any style except his

own, which doesn’t exist; he’d crossed the pond, immigrated to the Land of the

Free and the Home of the Brave from the European Theater in the 1950’s after

the Big War; a few close calls, he said, but not a scratch on him. While they

wait for noodle soup he’s been sketching a band of four Viet Cong

guerillas. Drawing from memory, a

picture he’d seen in Newsweek, humble farmers-turned-patriots who are

heroically kicking the stupid Invader-gangster Americans out of their country. “They don’t look like that,” Beale says. “Add fleas.

And they stink like hell.” Henri gives him his tricky grin. “I meant the egg roll.” Beale bites off the end of his roll. “Chicken tastes the same everywhere. Get it here, get it at Cheap Charlies.” “Where?” “Hai Ba Trung Street. Saigon. Chinese place.” “Chinks rule the world.” “Not yet, but some day.” “They’re kicking our asses, you know,” Henri says. “Tell me about it.

The Vietnamese are being duped and they’re going to lose their freedom

and end up in a commie hell-hole.” “Oh, come on, it can’t be like that.” “They’re fighting Russia’s war against us and they don’t

even know it.” “What you talking about, man?” Beale taps the sketch with his wet soup spoon. “You don’t fight troopers with sticks and rocks.” “Hey, respect the art, man.” “You made my point right there in your sketch. Not your fault; blame your photographic

memory. You drew in AK47s. Czechoslovakian. Transported east via the Siberian

railroad. And on south through China.” “That doesn’t mean anything…” “Sure it does. You

need guns to fight guns. Why the hell would the Russians send Czech guns to

help a bunch of stinking malcontents kill Nguoi My Sao? “Kill what?” “Ugly Americans.” “Huh. I don’t know…” “And another thing – notice how noble they look. A pack of godless killers, cut off school

kid’s hands so they can’t write in school, fucking baby rapers,

show up and kill every living thing in your house, even the cat and the

goldfish.” “Well, that’s the way they published it in the magazine.” “Right. In the 1800’s

people in Baltimore and Philly and London and Paris all thought Indians were noble savages. That’s the way they published it. Here we

have liberal assholes giving us noble

warriors. We’re being fucking played and we don’t even know it.” There is a loud bang.

One of the power drills outside has fallen against the plate glass

window in front. It sounds like a

grenade going off in the bathroom of the New York Bar on Hai Ba Trung Street,

like shrap banging on the outside of window glass at

the Café Monpelieu. Beale and Henri look at each other from under the

table. “Never goes away, does it,” Henri says, not really a

question. “No, it never does.” Beale doesn’t like to argue

the war, but everybody has an opinion, hawk or dove, and, of course, everybody

asks him. After all, he is a vet -- he's been

there, for Christ's sake, what does he

think? They'd get him going, but

that wasn't any good because everything he talked about from that far-away

world sounded so alien, so different from the short, disastrous

news-bite horrors that bled from the evening news. It is nearly impossible for them to relate to

what he is saying. It bothers them

that he can’t simply hate what we were doing over there; after all, what the

hell is this, Beale's War? Weeks became months and all the while the mounds of

remembered images grow in his pockets, his shoeboxes and

his mind, "Friend, FRIEND! You like suckie-suckie? Hundred P Alley just over there!" The street kids are half-naked and filthy,

and they swear like marines in marvelous bursts of pidgin French-English. The

country is great, like Florida,

he tells anybody who asks, and they look at him like he’s some sort of

idiot. Didn’t he know it was a hell-hole?

The Vietnamese are an incredible

blend of innocence and corruption, he tells them, and yet they can be good, loyal friends, and funny, too. And the average

guy on the street Beale’s talking to looks at him like he’s crazy. Jesus H. Christ, they’d be thinking, where was he making this stuff up from,

Gomer Pile? But Beale’s mind is already half way around the world. "Friend, friend, FRIEND! do you want to

eat rice-with-lice?" The

club-footed cripple laughs and shoves a Buddhist monk's wooden begging bowl at

him, and it’s crawling with maggots. Beale tries to explain something simple to the gay fat dude

who everybody said invented “Little Bill”, the power company animated light

bulb that looked something like a canary, tries to explain to him that a farmer

from the Me Kong Delta is no different than a farmer from Iowa – willing to

keep his nose out of everything as long as the sun

shines, the rains come, and the taxes aren’t too heavy. “Yeah, sure,” the chubby guy snickers, shoving an entire

Twinkie in his mouth and still able to talk around it. “And I’m Batman.” He

waddles away down the aisle toward the elevators, “Hey, hey, hey, Alfred, you

got my Batmobile ready yet?” She teased him with a lock of her long black hair, brushing

it against his cheek, "I new in from the

countryside, G.I. -- you want buy for me one Saigon Whiskey?" She was young and slim and mysterious, and he

had no way of knowing they would be having dinner on the floating restaurant

and he would see the white-gray mess of her brains blown in his face before the

year was out, that and her hair plopping into the large bowl of pho ga between

them. Beale’s listeners grow restless, and he can feel he is

losing them, and his frustration and the pitch of his voice rises. His Masters Degree

in Oriental Studies doesn’t help at all, nobody cares, they’ve seen the real

Nam on the nightly news, they even half believe about the evil G.I. troopers

who slaughter babies and execute cone hatted old ladies for fun, can of Schlitz

in one hand and a cowboy six shooter in the other. Beale sometimes shares a few sentences of

what he says is Vietnamese, and that doesn’t help either, a stupid, silly white

guy chanting the weird singy-songy language he

insists they speak over there. Here he

is in the heart of the good old U.S of A., making like - and yet unlike - some

yellow-skinned gook from China-land.

God-almighty, he makes everybody in earshot shift their feet and look

around, hoping nobody else is listening.

"Here's your dragon-dolly, Little Sweetbread, do you

want to go to bed?" Tuy was a few

months shy of 16, but none of them cared, least of all his friend Charley....

his friend Charley.... his friend Charley....

Once Beale thinks about Charley, he

goes into overload, and after that nothing helps, there is no way you’d want to

be anywhere near him. He tried to tell them how it really was, how we'd had our

chance to rescue a people and a land, how we really didn't want to win and they

really didn't want us over there, and how G.I.s were dying for nothing while we

were screwing everything up, and their blank stares drove him finally to a

numb, bitter silence. Hey, what's all

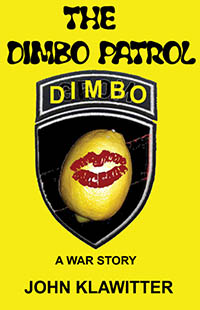

this shit about America Not Wanting To Win?? Was he for it or against it, for God's sake? Deep in Beale’s wallet, buried behind the wads of money and

credit cards carelessly stuffed in there is a frayed and fading military arm

patch with the letters DIMBO crested over a pair of ruby red lips painted on

the center of what looked like a common, ordinary lemon. This he never shows to anyone. In fact, he forgets it was there until one

time he is pulling out a twenty to buy a six-pack of Schlitz and when he sees

it his face goes white and he leaves his beer on the counter and rushes out of

the store, suddenly away in his other world.

Still, no question about it, Jack Beale is the

resident mad genius. When he gets the

idea to do the new Apple Cereal logo in finger-painting, he rents a stop-frame Boleaux and some lights and spends the night on the 13th

floor, breaking into the candy machine sometime after midnight and painting

with his own fingers on a glass partition in the reception area, making a mess

that was never really cleaned up until they replaced the carpeting. That little business cost over 5 grand, but

the new logo glows like stained glass, it is almost a religious experience if

you are into new product introductions, and so it was no trouble for them to

smooth over a few marks on the walls and get a guy to match the carpet. Instead of story-boarding his Sunrise Cereal

commercial he goes to a near North Side marina and films his vision with a

hand-wound 16 millimeter Bolex and some wanna-be

local actors, infuriating a department of talented art directors who see a

radical loner cutting through the system they depend on for their big

paychecks, and similarly outraging the agency producers who can imagine their

1st class trips to L.A. and New York City shrinking into cab rides to the local

labs to pick up rolls of processed film.

But the agency saved 30 big ones on that job, no small peanuts in those

days, and the business side mollified the creative grumblers with promises it

was a one-of-a-kind-thing. Later when the

kerfuffle died down, the production department found a little extra in the

annual budget and took his work and quietly re-shot it in 35 millimeter on the

West Coast; Beale doesn’t seem to care and nobody else notices, so everybody

ends up happy. The perky-boobed secretaries on the prowl for Mister Right leave Beale strictly alone,

and it isn’t just that weird marrying robe on his wall. The girls know he’s a hot flash, this week's

boy wonder and not the kind of guy you could count on for two kids (a boy and a

girl), a station wagon, a home with a big front lawn in Lake Forest and a bushy

dog named Flubster.

It only confirmed their first opinion when they learn he hangs around

with actor-types and mod painters and artsy-fartsy filmmakers and queer faggots

from the Lyric Opera and an assorted bag of weed-smoking loser-hippies,

undependable people who have the wrong demographics, which means they are not

important in the advertising world because they don’t buy mass-market things or

new homes in the suburbs. Jack Beale has intense, piercing eyes, old for his

thirty years, and a strange way of looking first at, then through and then

beyond you, a mannerism that makes him seem to drift inexorably from the person

being eyed to the mysteries of the universe, a stare that puzzles or

intimidates all but the most self-assured who cross what he calls the DMZ and

enter his office. He has two laughs; the genuine, amazed and

innocent laugh of a boy, which is heard rarely at the agency, and a sardonic,

brittle-rimmed chuckle that makes people uncomfortable. Of course, that was the one they hear most of

the time. And because he had all those

ideas and he really didn't care about anything, he hit a hot streak that

carried him through for a half dozen years, considered a long time in that

business. He had his problems, but that happens a lot in

the creative trade. There were the

erratic hours, the unexplained absences, sudden fits of rage, and shouting

matches with account types and clients.

There were the arrests for his all-night sit-in with a yellow and red

striped Republic of Vietnam flag on one of the bronze lions in front of the

Chicago Art Museum, another for breaking into the U-505 submarine, and another

time the police had come looking for some crazy fool who had dropped a glider

nose-weighted with a heavy can of rubber glue from the observation rim at the

top of the Prudential (it never did level out, falling like a stone through the

front windshield of a Checker Cab, startling the driver out of his gourd and

spattering rubber glue all over a well-dressed woman and her Carson Pirie Scott

packages in the back seat). And he had several outright breakdowns. The people at the ad agency patched him up, of

course. By the first time he'd gone off

the deep end he'd already invented the six million dollar Chocolate Village

campaign and the classic stop-framed Pop-Ups commercial which convinced a

generation of Americans that dry slabs of frosting-coated cardboard wheat with

a little strawberry jam in between was the fast and tastiest mod way to greet the day, and nobody

else could write the Fooper Bear Adventures that

explained to kids why their parents had to continue buying the soup with pasta

bits shaped like little bear paws. So,

after the cleaning ladies found him at three in the morning staring at a blank

television screen with his multi-colored marrying blanket around his shoulders,

the head of the agency sent him to a special lakeside retreat in northern

Wisconsin for a couple of months, where he was ostensibly location scouting for

a pool of menthol cigarette commercials.

It was an exclusive and well-kept place in the green-forested

pot-and-kettle hill-and-lake country.

There were miles of fenced-off woods to roam, bubbling brooks to

contemplate, and puffy white clouds to fall asleep under. That's how they'd put him back together. They'd wind him up and set him going and out

would pour Motown-singing plaster planets, cereal-stealing cartoon dogs,

box-top blimps and talking chocolate -- the wildest batch of crazy nonsense

ever used to sell a product. Sweet

Ecstasy, the bar that begs to be bit!

The candy mill in Chocolate Town makes candy bars so golden brown! Kids, Fooper Bear and his pal Old Man Vita-Mine, the good-health

prospector, say, "Now's the time to get out your Fooper-Dooper

spoons!" "When the sun comes up in the morning, time for Sunrise

Cereal!" It wouldn't last forever, but forever in The

Ad Biz, as they call it, is the next campaign, and while it did last it was

pure gold. They called it 'creativity' and excused him for caring

too much. His every excess proved their

point - nobody gave, nobody cared about the agency's clients, their products

and the American Way like Beale did. Jack Beale.

This is his story, a little bit of where he came from and some of how he

got the way he was. CHAPTER ONEAside from the sad and heavy weight of his disillusion with literary scholarship, what Beale will

remember most from his 1st year in UCLA grad school are the Kingston

Trio, the Maharishi who gave him his mantra, and the black girl from

Jamaica. The Trio reigned as his heroes,

and when they played Royce Hall in September of 1961, he tolerated the sweat

and thunder of the close-packed audience to hear all his favorites. The Trio lamented the green, green fields of

home, belted out the rousing Wake up Tom Dooley and the amusing MTA (Will he ever return?/No He'll never

return/and his fate is still unlearned/He'll ride forever through the streets

of Boston/He's the man who never returned), and the sad yet somehow funny

Sloop John B. (We came on the sloop John B./My grandfather and me/Around Nassau Town

we did roam/Drinking all night/Got into a fight/ I feel so break-up/I wanna go home) Getting drunk and thrown into a fly-specked jail in Tijuana

or a quaint island town in the Caribbean was close to the soul of the beat

generation, all those lost romantics searching for their own vague, sweet dreams

of a cherished promised land. That was

the way to live; that was the way to be.

Beale's blood pounded when he thought of loner James Dean,

leather-jacketed Marlin Brando, the burning intensity of Camus' stranger, or

the wild joy of thumbing down a desolate 2-lane highway like a Jack Kerouac

hero. It was heady stuff for the son of

a welder, a kid who had ground his way through a Mid-western college but had no

first-hand experience with a life of rebellion and real danger. The Maharishi Yoga is something else. The kindly-looking Maharishi, an East Indian

mystic. hits Southern California as a firestorm of enlightenment. He gifts Beale and fifty other hopeful young

souls with their individual mantra (fifty dollars each): their secret personal

word that enables each of them to find their spiritual center. They are mass-gifted at a group meditation

ceremony heavily laden with chanting, incense and the glow of candles. And then there is Mavis.

One night she crawled in through a window in his own small room in the

apartment building on hilly Strathmore Street near UCLA, stalking him down like

a savage she-beast from one his adolescent wet dreams. For a few brief months she becomes a player

in his life, and eventually proves to be the reason why he runs away and

enlists in the U.S. Army. For the rest

of his life he will tell himself something else, that he enlisted to see the

angry face of war like his hero Hemingway, but there was no way to deny Mavis

was a part of it. At first their joining was like a Midwestern adolescent

fantasy, but he came to be afraid she would devour him whole, leaving nothing

but dry skin and a few brittle bones.

For one thing, she practiced Caribbean juju, unpredictable and

unsettling. She is also violent-tempered

with political beliefs he finds alien and radical, and in the end he simply

feels lucky to get out of the relationship with his balls intact. Of his studies in graduate English, he remembers practically

nothing. Graduate studies in English weren’t anything like what he’d imagined.

Instead of honing his writing skills, he'd been buried in the dusty arts of

cataloguing and bibliography. And when

his advisor assigns him to a research project no one else wanted, he feels

something snap inside. For three days

over a long weekend he postured and railed at the mirror in his bathroom. Then

on Monday he went looking for his advisor. Beale could be patient and clever. He brought along a pillow, a six-pack of

Pepsi and Camus' La Peste and camped out on the tile floor in a dark corner

diagonally across the hall from Professor Vartig's

office. He would remain there overnight

if he had to. But when a pretty

undergrad hurried out of Vartig's door while

adjusting her skirt, Beale realizes his master is trapped inside and the moment

to act has arrived. He brushes past the

girl and makes his entrance before Vartig can think

to lock the door. The professor doesn’t seem surprised. He even nods occasionally through Beale's

lengthy rant. Beale pauses to catch his

breath and the professor finds what he’s looking for in a stack of beige

folders on his desk. "Ahh yes, here we are," he says with a sigh of

relief, as if Beale’s assignment might have been nearly lost forever.

"William Cowper and William De Fornay (or is

that 'Fornier'?)." He hands it across with a flourish, "I am sorry it is

so thin, Master Beale. That is why your skills are in demand. You must apply yourself to some classic

digging. Nobody seems to know much about

this De Fornay chap, and so I got to thinking, well,

they live in adjoining towns, they both are clerics, are both poets and

hymnologists, they both live at the same time, have flocks of sheep and a small

patch of greens -- maybe, just what if they end up being one and the same person!" Beale gingerly pushes the envelope away with the back of one

hand, "You haven’t heard a word I said.

I have a problem with this topic." "Which is?" "I don't want to know if Cowper is De Fornay, and I don't think anybody else does either." For the first time, the professor seems to take note of the

disheveled young man on the other side of his desk. "You, a 1st year graduate

student with a B minus average, choose to pass judgment on the celestial

hymnals of William Cowper." "No, I’m sure he is a fine poet, but it's just not

anything I'm interested in." "Hmm." Vartig clears his throat.

"Time to get serious about life, young Lord Beale. Do you realize the enviable life we offer you

here? "I could do something worthwhile." Beale grinds this last out stubbornly between

clenched teeth. Vartig sets the folder on the edge of his

desk near Beale. "How could you?

You're a professional student; you don't know anything about real

life." "I want a different topic!" Beale is surprised at the loudness of his own

voice. "Shhhhh. Yelling will get you nothing. You want your

degree; therefore, I own you. And

there is nothing you can do about it."

The professor gives him an imperious wave with the back of

his own hand, gesture for gesture, point for point. The interview is clearly over. |